Two years ago, when

Combined with equity investments from the country's largest banks, the massive injection of capital into dozens of minority depository institutions in particular — which have

But a combination of higher interest rates, higher deposit costs and post-banking crisis concerns about the safety and soundness of the nation's smaller financial institutions has put a significant damper on some minority banks' ability to attract and retain deposits. And without more deposits, some bankers say they cannot fully leverage the equity capital they have received.

Carver Financial, a Black-owned bank holding company based in Savannah, Georgia, needs at least $150 million of new deposits to make use of more than $25 million of capital it has on hand, said Robert James II, its president and CEO.

The company, which operates

One part of the company's strategy: Carver, which runs Carver State Bank in Savannah and Alamerica Bank in Birmingham, Alabama, hired a film production crew this past spring to visit customers and record them talking about how Carver is helping them to achieve their life and business goals. The clips are meant to show large depositors how Carver fulfills its mission-driven purpose and, ultimately, entice them to place their deposits at Carver.

Still, deposit-gathering "is proving to be a lot harder than we thought," said James, who chairs the National Bankers Association, a trade group for minority banks. "Impact investors are looking for rates, and that makes it more challenging to convince them to take a discount with us."

Minority banks' struggles to attract and keep deposits reflect

While most banks had been overrun with deposits during the pandemic, many of them later experienced outflow as rates ticked upward, and consumers, corporations and other depositors sought higher yields. In turn,

The struggle has been acutely felt by MDIs, which provide credit and other banking services to minorities and underserved communities. The sector has received large inflows of capital since the 2020 murder of George Floyd — including $3.1 billion awarded specifically to MDIs through the

Minority banks "had a lot of plans for those dollars," said Nicole Elam, president of the National Bankers Association, which represents 147 MDIs. While many of them have updated their technology, hired staff and increased their lending, they are still trying to secure all of the deposits they need to leverage the significant amounts of capital that many of them have raised, Elam said.

That includes some deposits that were pledged by corporations and other entities after Floyd's murder, Elam said. She explained that "a lot of loyalty is eroding" because more attractive rates have been available elsewhere.

At the same time, the pressure to pay higher deposit rates in the current rate environment means that funding costs have been rising. Like other banks, MDIs have had to pass those added costs onto borrowers by way of higher rates on loans.

And that's a big problem, Elam said.

Without more deposits, "that cuts into MDIs' ability to lend and have an affordable interest rate for their communities, which have historically already experienced higher interest rates," Elam said. "They want to be able to lend to those communities. They don't want to price them out."

In the banking industry, the rule of thumb is that for every $1 of Tier 1 equity capital on hand, banks raise $10 of deposits, which they can use to make loans. Deposits, therefore, are a crucial part of the equation for future growth.

Carver Financial understands that first-hand. Since 2020, the company has raised $22 million of equity capital — $15.9 million through ECIP, which to date has invested over $8.6 billion of equity into 175 MDIs and CDFIs, and another $6 million from big banks. The influx marked the first time that the company, which was founded in 1927, was able to raise equity outside of its own community, but the interest rate situation represented a curveball, James said.

"The high rate environment has made it more challenging to get mission-driven deposits into the fold at rates we can afford to pay, so that we can make loans to people in our communities at rates they can afford to pay," said James. "The impact is that it drives up the cost of borrowing, and we've got to pass that cost along, which then makes it harder for us to make a loan."

In addition to filming the testimonials from customers, Carver hired a chief impact officer who doubles as chief marketing officer, James said. The company is also making technology upgrades so that it can not only make loans in untapped markets, such as Atlanta, but also gather deposits there, he said.

Like Carver, Optus Bank in Columbia, South Carolina, has seen a huge increase in equity capital since 2020. The only Black-owned bank in the state, the $522 million-asset Optus received capital infusions from the likes of

Optus also raised $71 million through ECIP, and it got another infusion from MDI Keeper's Fund, a North Carolina-based private equity fund that was established in 2015 and completed its first MDI investment in December 2021.

In total, Optus has raised about $100 million of capital, President and CEO Dominik Mjartan said.

Despite higher interest rates and the deposit shifts that followed the failure of

So Optus is doing what it can to build relationships, in hopes that more deposits will flow in. And they are, albeit slowly. A year ago, the bank had $100 million of committed deposits in the pipeline, but most of those deposits didn't arrive until the latter part of the year, Mjartan said.

Part of the delay had to do with some depositors' uncertainty after the spring banking crisis about whether deposits at smaller banks would be safe, Mjartan said.

"I don't blame them," Mjartan said of those depositors. "That's a sense of the damage around [the bank failures]. They still felt like the risk was unknown, so they slowed everything down, and that slowed us down, unfortunately."

Some big banks and other large corporations are trying to help. Members of the Economic Opportunity Coalition, which includes eight large and regional banks, have

Having met its original goal, the group, which seeks to align private-sector investments in communities of color with related efforts by the Biden administration, is now trying to secure $3 billion of deposits from the corporate sector.

Potential targets include other banks, as well as other Fortune 500 companies that manage cash, including endowments and private equity firms, said Chris Weaver, who is the EOC's executive director.

Ultimately, MDIs and CDFIs that received equity capital through ECIP will likely need around $25 billion to $30 billion of new deposits, Weaver said. "We have a lot of work ahead of us," he said.

The pledge was part of

In September 2022, after the ECIP awards were doled out, the bank decided to double its deposit commitment to $200 million, said Dan Letendre,

"It really is a question of deposits right now," he said. "Eventually these banks are going to have to open new branches … but for now, deposits are desperately needed, until they can grow into the equity, and then they can raise [deposits] more organically from their communities."

"The first bank that got our deposits sent me a note and said they were able to turn the spigot on" and start making loans right away, Butler said. "They moved on $15 million of new loans that were ready to go, and I just thought that was remarkable. They were able to turn it loose."

Aside from its own pledge,

"We're showing them how we've done it, and now they're going through the process themselves," Butler said. "Because in order for this to work properly … it takes a village."

The company hasn't joined the Economic Opportunity Coalition because it has felt there is a "commonality in the objectives" of

As for whether

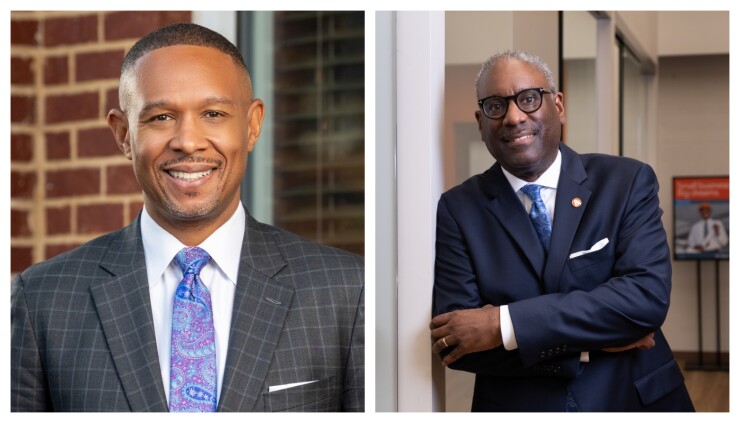

Like Carver, M&F Bank is taking extra steps to attract deposits. Headquartered in Durham, North Carolina, the Black-owned bank has since 2020 received nearly $100 million of capital — about $18.5 million from big banks and $80 million through ECIP — for a total of $121 million today, said James Sills III, its president and CEO.

The $358.3 million-asset company has eight branches, all in North Carolina. It has focused much of its deposit-gathering efforts on the markets in which it currently operates. During the fourth quarter of 2023, M&F ran a campaign to try to pull in at least $7.5 million of new deposits. By offering a money-market rate in the 4% range, the bank expects to exceed its goal by 50%, Sills said.

Also during the fourth quarter, M&F received $10 million of deposits from a company participating in the Economic Opportunity Coalition, which Sills declined to name. Still, there's a lot of work to do and a long way to go, he acknowledged.

"We're looking for low-cost deposits that are sticky and long-term, and we have some great depositors — banks, corporations, nonprofits — that understand our mission and all the things we do," he said. "So we're telling our story, and that's helping us gather those deposits."

One way that more deposits might wind up flowing into minority banks is through revisions to the Community Reinvestment Act, said Brian Argrett, president and CEO of Broadway Financial, the holding company of City First Bank in Washington, D.C.

Argrett runs the first Black-led bank to cross $1 billion of assets. The company raised $150 million of capital through ECIP, plus another $33 million of private capital in conjunction with its 2021 merger with Broadway Federal Bank in Los Angeles. The bank is now in a position to grow substantially if it can fully leverage all of the capital it has on hand, according to Argrett.

Argrett said the CRA revisions should help "steer more deposits" into MDIs and CDFIs because the new regulations will include incentives for larger banks to place deposits in those institutions. In the near term, there's an expectation that potential interest rate decreases by the Fed could result in some margin relief, as rates normalize and loan demand increases, Argrett said.

But MDIs can't be the only ones telling their stories, said Elam of the National Bankers Association. Big banks can help, as can large corporations. Lawmakers also have a role, she said.

"You really need to get people to understand a mission rate versus a market rate," Elam said. "I think it's going to require more than MDIs talking about it. We need more of corporate America telling the story of why it's important, and then we need policymakers to do their part too."