Want unlimited access to top ideas and insights?

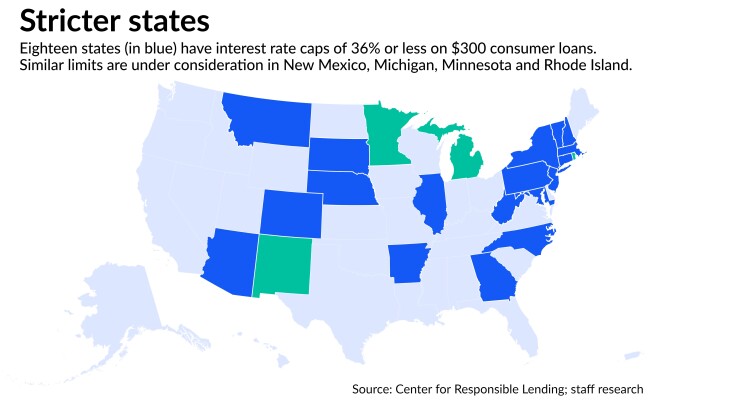

With efforts to implement a national rate cap stalled, more states are weighing bans on consumer loans with annual percentage rates above 36%.

Lawmakers in New Mexico recently approved a 36% rate cap, which would slash the state’s current maximum APR from 175%. It now awaits the governor’s signature. Legislators in Rhode Island and Minnesota are considering similar restrictions, and consumer advocates in Michigan are

The state-level action comes as congressional

Consumer advocates still hope lawmakers will give all consumers “the same kind of protection that Congress thought was needed” for military members, said Yasmin Farahi, senior policy counsel at the Center for Responsible Lending.

But advocates are also working at the state level to cap interest rates at 36% — or lower. Doing so would help prevent borrowers from being “caught in the payday debt trap,” where they are unable to repay triple-digit APRs and end up owing far more in interest than they originally borrowed, Farahi said.

Many states across the country allow payday lenders to charge APRs above 300%, and Texas, Nevada and Idaho allow annual interest rates above 600%, according to a

“These are marketed as a quick financial fix, but actually lead to long-term financial distress,” prompting consumers to miss other payments and even driving some into bankruptcy, Farahi said.

Trade groups that represent payday lenders and high-cost installment lenders — whose loans are larger and spread out over a longer period of time — are pushing back against those efforts.

They take issue with the focus on APRs as the proper gauge of a loan’s costs, arguing that it is an inappropriate metric for shorter-term loans. They also say that the high fixed costs of making small-dollar loans drive APRs above 36%, and that the prices reflect the risk of offering credit to people whose low or nonexistent credit scores often prevent them from getting traditional bank loans.

Rate caps will limit lenders’ ability to operate in certain states, giving consumers “fewer credit options at their disposal to meet their needs,” said Andrew Duke, executive director of the Online Lenders Alliance, whose members include high-cost lenders like Elevate, Enova, Axcess Financial and CURO Financial Group.

INFiN, a separate trade group that represents payday lenders with branches across the country, said in a statement last month that New Mexico’s rate cap will “leave consumers with little choice but to turn to the costlier, riskier, and less regulated alternatives” for credit.

New Mexico lawmakers

The rate cap is expected to add New Mexico to the list of 18 states that have stringent limitations on small-dollar consumer loans, according to the Center for Responsible Lending. Those states include

In 2019, California

Last year, Illinois

The growing number of states looking at rate caps is among the “numerous headwinds” facing high-cost lenders, even if many states do not follow along, said Isaac Boltansky, a policy analyst at the research firm BTIG.

High-cost lenders are also facing the potential for more scrutiny from the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau, Boltansky said, as well as the potential that the Federal Deposit Insurance Corp. will take a tougher stance on partnerships between banks and nonbank consumer lenders.

In some states, high-cost lenders make loans directly to customers. But in states with more stringent limitations, they often partner with FDIC-supervised banks — which critics decry as “rent-a-bank” arrangements aimed at evading state rate caps.

Consumer advocates recently

The agency “appears to have done nothing to curtail the predatory lending that has exploded on its watch,” the National Consumer Law Center and 14 other groups wrote in a letter to the FDIC board, in reference to the tenure of former Chair Jelena McWilliams, a Republican appointee.

The consumer groups note that high-cost lenders are charging interest rates they would not be able to charge on their own, because their partnerships with a few small FDIC-supervised banks enable the exportation of the banks’ home-state interest rate rules.

The Online Lenders Association pushed back last week against the effort, writing in a letter to FDIC board members that the partnerships help community banks make loans beyond their traditional footprints.

They also wrote that fintechs’ expertise in underwriting loans to consumers who struggle to get traditional loans helps their bank partners to reach new customers.

“Fintech companies working as third-party vendors for banks can play an important role in building a more inclusive financial system for consumers,” wrote Duke, the group’s executive director. “These innovations can pave the way for future improvements that will broaden credit opportunities and improve consumers’ credit options.”

The FDIC, currently headed by acting Chair Martin Gruenberg, declined to comment on the issue.