-

Fidelity Southern (LION) in Atlanta has filed documents that would allow it to issue up to $100 million in stock, warrants and debt.

April 4 -

Seacoast Banking Corp. of Florida (SBCF) in Stuart has filed a shelf registration to issue up to $150 million in debt and securities.

March 21 -

It's unlikely that SunTrust Bank wanted to become a part owner of a small North Carolina bank when it made a $15 million loan nearly three years ago.

January 7

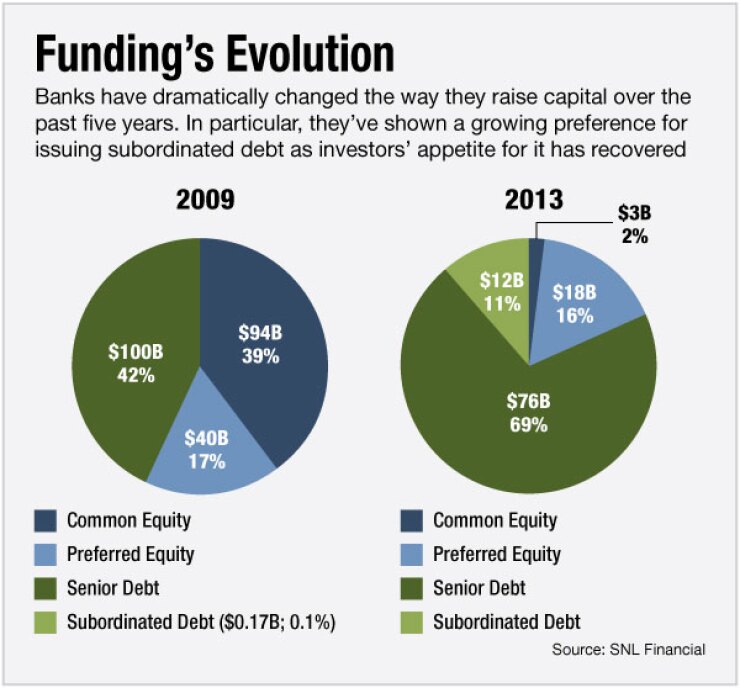

After a lengthy fast, investors are once again hungry for subordinated debt.

There has been a surge in the issuance of subordinated debt in the last year, the first serious activity in the market since it ground to a halt during the financial crisis. Low yields across the fixed-income spectrum have caused investors to reconsider sub debt, which is riskier than senior debt but usually offers a higher return.

This renewed demand has given community banks a way to raise capital more cheaply than through a stock offering. It also helps fill a funding gap left by the demise of trust-preferred securities.

"Sub debt hadn't really been an option over the last six or seven years, but it has started coming back as a vehicle for community banks in the last six months or so," said Lee Bradley, managing director of Community Capital Advisors. "The feeling among investors is that it's safe to get back into community banks again."

Smaller banks now have more options for capital than at any time since 2008, and they have responded by ramping up issuance of many fixed-rate instruments, including senior debt and

Still, subordinated debt is making a comeback. Last year, public U.S. banks and thrifts issued about $12.3 billion in subordinated debt, according to SNL Financial. That's more than four times the $2.8 billion of total sub debt those banks issued from 2009 to 2012. It also dwarfs the $2.7 billion in common equity that public banks issued last year. (The data does not include unregistered offerings and sub debt issued by privately held banks.)

There are several reasons why some banks prefer subordinated debt over equity: sub debt does not dilute existing shareholders; interest payments on sub debt, unlike dividends on preferred stock, are tax deductible; and the funds raised count as Tier 2 supplementary capital at the holding company.

The key, however, has been renewed interest from investors. After years of being worried about bank survival, investors are again willing to tolerate the risk of sub debt, which generally ranks below senior debt but ahead of equity in the event of a bankruptcy, in exchange for higher returns.

"The desire to issue sub debt was always there, but the investors weren't," says Jefferson Harralson, an analyst with Keefe Bruyette & Woods.

The financial crisis drove investors away. In several high-profile failures, including Lehman Brothers and the Icelandic banks, subordinated debtholders were wiped out. Bond-rating agencies responded by downgrading the debt of surviving institutions. Large and regional banks, once key players in the market for community bank sub debt, pulled back their bank-to-bank lending.

These shifts left many banks especially smaller ones frozen out of the bond market. Public banks issued just $170 million in sub debt in 2009, according to SNL.

The fixed-income profit squeeze has revived the market, says Peter Weinstock, a partner at Hunton & Williams. "In light of how low interest rates are and the demand for yield, there has been a lot of excitement among the investor class for subordinated debt," he says.

Institutional investors in particular have sought out community bank debt in the past year, helping revive the market. There has also been a growing willingness of retail investors to buy and retail brokers to sell community bank debt.

Several community banks have responded by conducting sub-debt placements in recent months, including

Community banks generally issue sub debt through retail offerings "friends and family" sales or broader community offerings or targeted issuance to institutional investors.

Interest rates are lower for retail offerings. Weinstock says rates generally run from 4% to 6% for retail issuances and from 7.5% to 9% for institutional offerings. The choice between a retail and institutional offering is a trade-off; while the cost of capital is lower in a retail offering, it can prove harder to line up buyers.

"I always tell a bank that if they can get a local deal at they should do that," says Josh Siegel, chief executive of StoneCastle Partners. "A community banker recently told me he could do a retail offering at 6%, and I said, 'You should grab that. JPMorgan can barely get that rate.'"

Siegel is one of several institutional investors whose appetite for small bank debt has helped stimulate the market. Last year, Siegel

EJF Capital in Arlington, Va., also launched a sub-debt fund last year. EJF generally invests $4 million to $15 million in five-, seven- or 10-year community bank sub debt; the company would not disclose the total amount it has deployed since its fund was founded. The investments are usually in "private institutions that don't have great access to capital" and either want to refinance existing debt or grow, says Heather Rosenkoetter, an EJF managing director.

NexBank in Dallas offers a twist, issuing term loans, usually between $1 and $10 million, with the borrower's stock as collateral. The company has closed about a dozen such deals in the last year, says Matt Siekielski, NexBank's chief operating officer. Two recent recipients of NexBank loans are FNB Bancorp (FNBG) in South San Francisco and Intermountain Community Bancorp (IMCB) in Idaho.

Many banks issuing sub debt right now simply don't have access to senior debt and want to retire higher-cost funding. But demand should continue to rise as long as bank profits improve and as the long-expected consolidation wave appears, says John Roddy, head of Macquarie's financial institutions group.

"Sub-debt issuance is usually case-specific or transaction-specific, because growth remains slow and M&A remains slow," Roddy says. "But there is no lack of investor interest."

Basel III requirements

"Sub debt can lower your cost of capital and increase your return on equity," says KBW's Harralson. "Most banks have excess common and preferred stock and don't need to add sub debt to their structure right now, but at least the option is back."