Digital allowance. Customizable debit cards. Goal-setting and saving with interest paid by parents or the bank.

These are some of the top features that exist in challenger banks for Generation Z, or those born in 1996 or later, but are largely absent from traditional banks’ offerings for young customers. A year ago, a

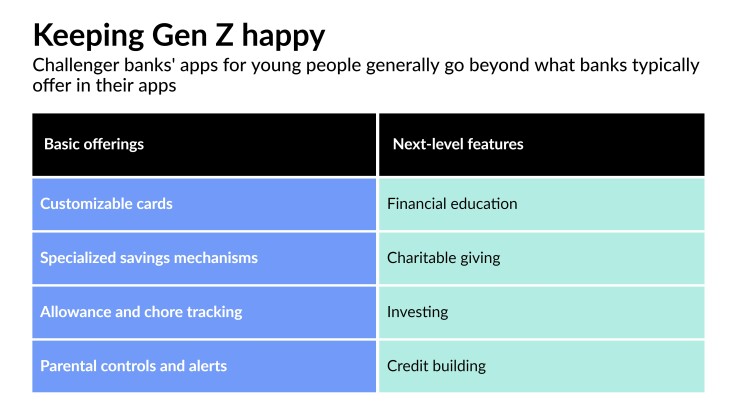

These apps tend to follow a formula:

- A debit card that the user can customize with a name, image or color

- A savings account that nudges kids to set goals and provides mechanisms for loved ones to chip in

- The ability for parents to transfer allowance dollars to their child’s card and tie these payouts to household chores

- Parental control over where kids spend money and how much they can withdraw

- Increasingly, financial education in the form of quizzes or articles, ways for children to donate to charities and the ability to invest in fractional shares of stock

Some banks have also used creative means to target the same generation, such as JPMorgan Chase with its

But banks have largely been slow to follow suit beyond generic checking and savings accounts for children that largely mirror their regular accounts, and Gen Z has shown a propensity for switching banks when it suits them.

A recent study by the research firm Raddon found that about 70% of both millennial and Gen Z consumers are customers of one of the six largest banks in the U.S. “But there is still a significant risk for Gen Z switching to fintech because they are very comfortable with fintech,” said Karen Kislin, a strategic advisor at Raddon. The study also found that about a third of millennials and Gen Z are extremely or very likely to choose a new primary financial institution in the next year.

“Banks have to do more in this space,” said Alex Johnson, director of fintech research at Cornerstone Advisors. “They risk new generations of customers getting steered to providers other than themselves.”

These apps are already winning over millions of users. Gohenry, which originated in the United Kingdom, has 1.5 million global customers. Step advertises 2 million customers on its website. Greenlight, perhaps the most robust of the bunch with three tiers of plans, exceeds 3 million users.

Banks have several advantages over fintechs, including a more personal connection to their customers and the ability to meet face to face, which members of Gen Z prize alongside digital capabilities, said Kislin. They also have trusted brands, points out Matt Williamson, vice president of global financial services at the digital consultancy Mobiquity.

The features Gen Z wants most

Many millennials grew up with their parents handing them coins or bills for their weekly allowance. Challenger banks are turning that ritual into something seamless and digital, almost by necessity.

These days “you’re not going down to the candy store,” said Johnson. “You’re going online and streaming stuff, buying new outfits for your video game character. Everything is digital where kids are spending money.”

Transferring allowance via an app lets parents balance oversight of the money with giving their kids some freedom to handle it themselves.

“Customers always tell us they want to get into an allowance regime because they believe that’s a big part of helping kids manage a budget, but with cash they often forget or don’t have the right change,” Dean Brauer, co-founder and president of gohenry, said in a 2020 interview. “When you make it automatic, it builds that consistency.”

To create a sense of ownership over their spending, many of these apps also let kids customize their debit cards with a photo or color. Greenlight even has a “black card” for its Greenlight Max tier.

Personalized cards may sound like a minor benefit, but “this makes it feel like it is their own,” said Johnson.

While encouraging kids to spend responsibly, these apps also emphasize the importance of saving by setting and tracking progress toward goals.

Till lets parents bolster children’s savings by matching the child’s contributions by a set percentage or by paying interest on the balance. Relatives and loved ones can also transfer money, match contributions or pay interest. Similarly,

“The larger thing you are trying to impart to kids is the compounding value of savings,” said Johnson. “Regardless of the specific features and how you design it, you want to show kids that if you have patience, there is a big reward that builds over time.”

Financial education is another component that may or may not immediately grab kids who use these apps. But it’s important to have, said Williamson, because as spending takes on an increasingly digital form, it becomes less tangible than cash. He finds gamification to be particularly effective.

Goalsetter incorporates quizzes peppered with pop-culture memes and GIFs into its product. A Learn Before You Burn function lets parents freeze their child’s debit card on Sunday if the child has not yet taken that week’s quiz while Learn to Earn lets parents pay a small bonus to their child for every quiz question they answer correctly.

Finally, most apps let parents hold the reins behind the scenes, letting them dictate how much can be withdrawn from ATMs or spent on a daily or weekly basis, and where this money can be spent. Or the app may block purchases from certain retailers altogether, such as liquor stores or adult sites. Some apps send the parents alerts about their child’s activity.

Johnson divides these challenger banks into two categories. Some, like Greenlight and Till, “are targeted at kids and teens but really built for parents,” he said. They provide a safe space for kids and teens to learn about money management until they are ready to take control of their own financial lives.

The second type are in the vein of

“Most of Current’s customer base is early- to mid-20s on average, but as they age into needing more complex products and loans, my expectation is Current will grow into a broader set of products to serve those customers,” said Johnson. “They are never intending to let those customers graduate off that platform.” He foresees Step as building a similarly lasting brand.

Features on the horizon

With gohenry, kids can direct 10 cents to 25 cents a week to the Boys and Girls Clubs of America. Greenlight customers can research and donate to charities through a link to CharityNavigator.org.

“Charity is incredibly important because Gen Z is very socially conscious,” said Williamson. He finds that if charitable giving is set up as a regular payment, similar to a monthly subscription to Netflix, Gen Z is more likely to participate.

Investments are also slowly making their way into fintechs for Gen Z. BusyKid, for example, has a partnership with Stockpile that helps users purchase full or partial shares with a minimum of $10. Greenlight, a registered investment advisor, lets users buy fractional shares with as little as $1. It partnered with DriveWealth to execute the trades.

Such features let kids dip a toe in with products they are already familiar with, such as Apple or Nintendo, and learn they don’t need a lot of money to start investing.

At some point, banking apps for this population may want to consider incorporating cryptocurrencies.

“Gen Z is very much aware of this big cryptocurrency environment and are likely to own some cryptocurrency or be interested in obtaining it,” said Kislin. “That is the next frontier for the banking world.”

Both Johnson and Williamson expect to see more partnerships between banks and these fintechs, where banks could leverage the user experience the neobanks have refined. This may come in the form of acquisitions, strategic investments, white-labeling or other means of collaboration.

These partnerships have already begun. The collaboration between JPMorgan and Greenlight is one example; the work Goalsetter is doing with several financial institutions to sponsor Goalsetter accounts in their communities to fulfill Community Reinvestment Act requirements is another.

When developing Gen Z-friendly accounts of their own, banks may have more to think about than specific features.

“Don’t think of Gen Z as one monolithic generation,” said Johnson. “6- or 7-year-olds are not anywhere close to being a prime banking customer. When they are 18, what will their expectations be for how banking works and what would they be open to that would be inconceivable today?”