-

Community banks sustained a 27% decline in mortgage banking income last quarter, confirming the laments of individual banks during earnings season. Some banks are getting creative to try to revive their business in coming quarters, but it will be tough.

November 5 -

In an earnings call, FIS CEO Gary Norcross articulated a trend weve been following for several months: banks are charging for certain mobile banking services and getting away with it.

October 30 -

Smaller banks are beginning to see more revenue from service charges as they experiment with new fees and products.

February 5

Charging fees for services is becoming a necessary evil for community banks.

Regulation has constricted the revenue banks generate from areas such as overdraft protection, while the

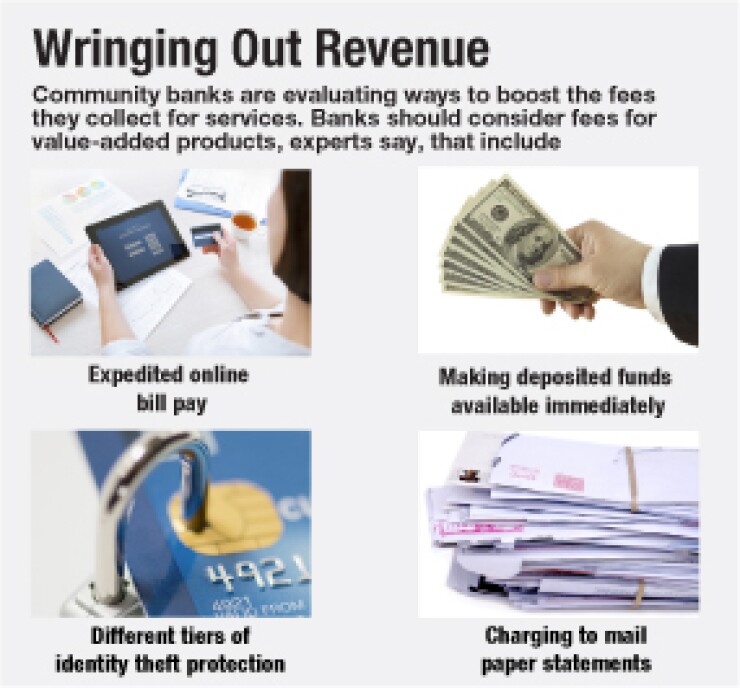

Many bankers are rethinking their fee structures and the range of services they provide. The trick is to avoid overly punitive fees, while offering services, such as expedited online or mobile bill pay, that offer value to customers, industry experts say.

"It is about how the fees are structured," says Dan Geller, executive vice president at Market Rates Insight. "When you talk about fees, people automatically assume you have to charge a fee and that's the only option. Instead, you should offer customers choices."

Assessing fees can backfire on a bank, as demonstrated by Bank of America in 2011, when it announced and subsequently nixed after widespread backlash plans to charge

Banks have been "giving away so much for so long that now if they charge a reasonable fee it can be difficult," says Trent Fleming of Trent Fleming Consulting. "Any fee is perceived by the consumer as unfair. Banks haven't done a good job of promoting the value of a service."

"Fees are still a hot button for customers, so we've been reluctant about adding fees," says Susan Still, president and chief executive of the $392 million-asset HomeTown Bank in Roanoke, Va.

Bankers have several ideas on how to research and implement fees.

It often makes sense to canvass a market first, to see what fees are being charged at other banks, says R. Van Bogan, chairman of the $228 million-asset Florida Bank of Commerce in Orlando. A bank might be able to get away with a fee on a product or service if most, if not all, other banks in a market are assessing one, he says.

Banks also stand a better chance tacking fees onto newly introduced products, says Thomas Boyle, vice chairman at the $590 million-asset State Bank of Countryside in Illinois. In contrast, "you can't go back and charge a new fee on an old product," he says.

Another strategy involves providing tiers of service that have different fees, Geller says. For instance, it normally takes two or three days to process a remote deposit capture transaction. Banks can continue to offer that option for free, but incorporate a fee for clients that need those funds immediately or overnight, Geller says.

Banks that are preparing to implement remote deposit capture should consider charging a nominal fee, such as 50 cents, for basic level service, Geller says. Clients are generally willing to pay a small fee since remote deposit capture is more convenient than the free option of driving to a branch or ATM to deposit a check.

Regions Financial (RF) in Birmingham, Ala., has

"This is attractive because customers are not forced to do that," Geller says. "It is an option. We all appreciate options."

The same rationale could apply to services such as expedited online bill pay, industry experts say. Banks could offer a basic option for free but assess fees for expedited payment processing. Also, tying free checking to products like receiving electronic statements can drive desired customer behavior and control costs.

Banks could also implement fees for the extra work they do for clients. Some banks have moved funds from a customer's savings account to a checking account to help the person avoid an overdraft charge, says Lynn David, president of Community Bank Consulting Services. Customers could move those funds on their own but, since the bank is assisting, executives should consider charging $7.50 to $10, an amount that is less than a normal overdraft fee, he says.

Community banks frequently provided services, such as handling returned mail when a customer moves, that take more time for staff to complete. Some banks are starting to look at charging a fee for that service, David says.

Overall, it is important for banks to clearly communicate to clients why they need to charge a fee while suggesting ways to avoid them, industry experts say.

"Customers should have alternatives," David says. "You can either take some steps yourself to complete the transaction for free or you can have the bank handle it for a fee. I believe in choices and as long as you give customers choices, they don't typically get upset."

Lenders at community banks are also quick to waive late fees on loan payments, Fleming says. This should be stopped, though doing so usually requires changing a bank's culture, he says. Fleming says he has worked with banks to implement a policy where lenders must explain the waiver to their peers, which typically curbs the practice.

"You can justify not waiving a late charge on a late payment," Fleming says. "If you can demonstrate why there is an extra charge then there shouldn't be any complaints and there shouldn't be any publicity about this big evil bank charging this fee now."

Paul Davis contributed to this story.