Bank of America's blockchain patent push shows how bankers' attitudes toward the technology of cryptocurrencies have changed over the last few years — from dismissing it, to sizing it up to trying to protect their interests in it.

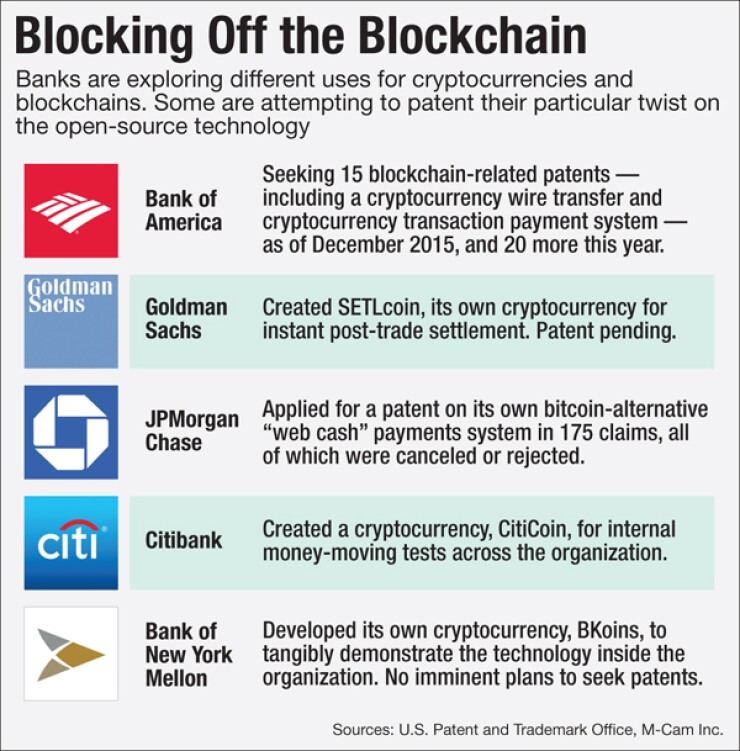

B of A is seeking 20 blockchain-related patents in addition to the 15 it previously filed in 2014. The move raises questions about the legality of patenting software whose original code is open source: free for anyone to access, use or modify. Blockchain technology has been touted as a potential game-changing technology for the banking industry. But as the once obscure technology inches closer to the mainstream, bankers are essentially trying to establish a legal framework for blockchains.

"'We want to patent so … we don't have to worry about getting sued because we have the IP,' is one way to justify B of A's patent strategy," said Brian Knight, associate director of the Milken Institute's Center for Financial Markets. "The other is due diligence, where they don't know if it's patentable… if they try and the [U.S. Patent and Trademark Office] refuses on the grounds that it's not, they know they won't be sued by anyone else."

-

Bank of America is preparing to submit 20 blockchain-related patents any day now to the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office, CNBC reported this week, citing a company spokesperson.

January 29 -

Goldman Sachs is seeking to create its own cryptocurrency for post-trade settlement, according to a recently released patent filing.

December 3 -

Major cloud, consulting and software providers like Microsoft and Deloitte are plugging "blockchain as a service" for financial institutions that want to experiment with this technology without making huge investments.

December 8 -

The latest blockchain technology initiative has IBM, Digital Asset Holdings, R3 and other tech companies working with banks, Swift, the London Stock Exchange and the Linux foundation to jointly create open-source software meant to be used to quickly bring new blockchain software to market.

December 17 -

Banks used to have almost no involvement with the U.S. patent system, but recently some large institutions, like Bank of America and JPMorgan, have begun locking down intellectual-property rights. The effort appears to be aimed at fending off patent trolls, and it raises fresh questions about which activities are legitimate for financial institutions.

July 2

The bank's strategy is pragmatic, observers say. Even if it hasn't yet determined what blockchains' commercial use would be for it specifically, it's smart for companies to protect their intellectual property early.

"You can take open source code, modify it and patent around the modification of it," said Carol Van Cleef, a partner at law firm Manatt Phelps & Phillips. "It's really a race to the courthouse."

What really matters is how much different B of A's claims are than something else that already exists. That it filed a patent application at all comes with the assumption that it has an interesting twist on the technology.

"The scope [of the patent application] would have to be limited to the specific new feature that they add," said Paul Overhauser, managing partner at Overhauser Law Offices, a firm that specializes in intellectual property cases. "They could not get patent protection so broad as to give them any patent rights to the original source code idea of having a blockchain."

Bank of America did not respond to calls or emails, but Cathy Bessant, its technology and operations chief, discussed the patents at a CNBC event in Davos recently. Bessant has been vocal about the bank's overall strategy in patenting technology — for instance, she touted its place as one of the top 10 patent holders of bank-related patents in a

"Our patents and awards portfolio is at 2,800 and climbing, and we are frequently cited in patent applications by the likes of Apple, eBay, Google, and Microsoft," she said.

Because of bitcoin's open source nature, banks can't patent its software. They would have to build somethingcompletely new and useful.

"If they have a unique process that they utilized the blockchain for, but the actual process itself is novel, then it is possible they could patent that process," he said. "They don't get any user IP claim to the underlying blockchain but they do for their unique process, for whatever they're building on top of the blockchain."

Banks are currently exploring how they can use blockchain technology for their own commercial gain, by creating their own iterations of bitcoin for internal testing. Bank of New York Mellon, for example, created BKoins to learn more about the technology and demonstrate it across its organization. Citibank did the same in creating CitiCoin. (Neither of those companies sought patents for their creations.)

Though blockchains are repeatedly touted as disruptors to the banking industry, long wary of its unchartered waters, Van Cleef said they may just be the next wave of something the industry is already used to: another funds transfer network.

"The banks have a long record of collaborating with each other — especially since they need to interact efficiently to facilitate payments and interbank transfers. Swift, ACH, FedWire and even the credit card networks are a testament to such collaboration," she said. "This could be next generation of such interaction."

Until individual banks figure out what blockchains' successful commercial use will be for them, it's no wonder they'll want to preserve whatever intellectual capital they have. Van Cleef predicts they will continue filing patents around them, if they're using open source code, but that by virtue of being open source, the code won't prevent anyone from going in and using it.

"We should expect that we're just going to see more of this — more patents being filed, especially as people are working on proprietary projects."

Overhauser agreed.

"Even if they don't know it's going to be a commercial success, that's just a standard process of protecting your IP," he said.

The key to the blockchain's success is adoption by a large number of people, he added. The big banks see the writing on the wall; that this technology will eventually become more favored, and to the extent that they can come up with their own iterations of cryptocurrencies and get them accepted in the market place, they would have a leg up on their competitors.

"Large financial institutions have tried to be dismissive of cryptocurrencies and blockchain technology, but [the interest] just continues to grow and grow," he said.

B of A is at least the third bank to pursue cryptocurrency-related patents. In December the USPTO published a filing by Goldman Sachs

In December 2013, 175 patent filings by JPMorgan Chase for

One of bitcoin's appeals has been the elimination of mediators in opening and closing transactions for a profit. To bitcoin's earliest adopters, there may be something perhaps invasive about financial institutions — who not so long ago outwardly disregarded cryptocurrencies — looking to occupy blockchain's open source territory.

"There's a real philosophical divide with respect to open-source coding," Van Cleef said. "Those who buy into the concept are religious to the concept."