Hundreds of security threat reports come out every year from security vendors. We see at least two a month. Most focus on the single type of threat that the sponsoring vendor happens to offer protection against and are thinly veiled marketing pieces.

Verizon's Data Breach Investigation Report is different. The telecom giant creates it in concert with more than 67 organizations, government agencies among them. Notable contributors include the U.S. Secret Service, the U.S. Emergency Computer Readiness Team, the Anti-Phishing Working Group, the National Cybersecurity and Communications Integration Center, Kaspersky Lab, Cisco Security Services and EMC. The 85-page treatise covers many areas of security for which Verizon doesn't sell products.

This year's report covers more than 64,199 incidents, of which 2,260 were confirmed data breaches. About 1,368 of the incidents and 795 of the confirmed breaches occurred in the financial services industry.

-

The inadvertent downloading of thousands of consumer records to a thumb drive at the FDIC could happen anywhere. Here's a look at what the FDIC did right and what it could have done better.

April 14 -

The tax agency's struggle to protect sensitive data mirrors banks' own, and its shortcomings can also be found at financial institutions.

March 8 -

Hackers did not steal banking or payments data from Experian, but they might as well have. Breaches like the one sustained at the company call into question the entire system of identification that banks rely on to open accounts and conduct other everyday business.

October 2

The report doesn't include every security incident that occurred in 2015, but it's the broadest, most thorough look at breaches we've seen. Here are the key takeaways for banks:

The motives for data breaches are increasingly financial. This obviously makes banks more of a target than ever. The report found that 89% of breaches in 2015 were motivated by greed or espionage rather than, say, getting back at a former employer or sticking it to the Establishment.

"This year's report is more weighted toward financial motivation than ever before," said Chris Novak, director of investigative response at Verizon Enterprise Solutions. "We've looked at different motivations — financial, espionage, and other categories like fun, ideology, or grudge. You've seen a lot of those other categories die down."

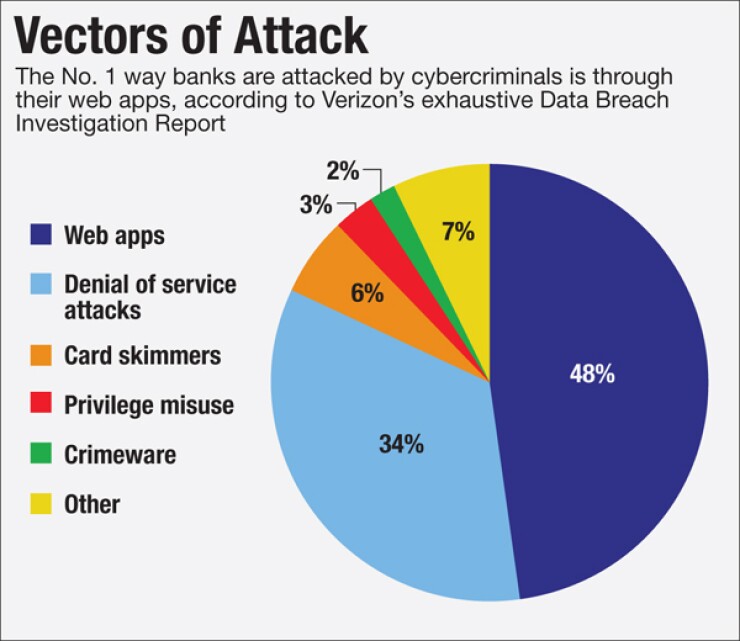

Banks are getting hit hardest in their web applications. Forty-eight percent of bank data security incidents in 2015 involved compromised web applications, the Verizon report found.

Some apps are compromised through code injections. GozNym malware, for instance, typically inserts code into banks' websites that creates pop-up screens asking for personal information. Through

Web app attacks are hard to detect since banks have thousands, sometimes millions of legitimate users accessing their sites. Finding the bad behavior in the noise is difficult, especially if the cybercriminals use multiple

The best defense?

Hacktivism has died down; distributed denial-of-service attacks have not. The second most common security incident for banks in 2015 – 34% of their total – is the distributed denial-of-service attack. Banks have not been hit with a wave of activist DDoS attacks like the one we saw in 2012, when the Al Qassam Cyber Fighters relentlessly targeted dozens of bank websites to protest a video on YouTube.

Yet DDoS attacks, those malicious streams of traffic aimed at websites to shut them down or at least cause slow performance and embarrassment, continue to increase, partly because they're easy and cheap to do. The attackers typically use compromised systems organized in

"Because it's inexpensive and occasionally they manage to hit something, they just keep doing it, and every now and then it works," Novak said.

Financial institutions continue to get better at deflecting DDoS attacks. After the 2012 attacks, many bought better mitigation tools.

The starting point for breaches is usually phishing, the sending of emails with malicious attachments or links that allow malware to be downloaded to the user's computer, or that fool users with their message to share sensitive data. In 2015, 9,576 security incidents involved phishing, and 916 of them had confirmed data disclosure.

The report states that in tests, 13% of people clicked on a phishing attachment. The median time for the first target of a phishing campaign to open a malicious email was one minute and 40 seconds; the median time to the first click on an attachment in that phishing email was three minutes and 45 seconds.

Do people need to just slow down?

"A lot of the problem is the speed," Novak said. "You look at an email and almost click on it because there's a sense of urgency and you're probably like everybody else wearing five hats."

Email filters are of limited use because the malicious attachments usually appear to be normal Word, PowerPoint, Excel or PDF documents. "If you were to filter out all PDFs, most organizations wouldn't be able to function," Novak said.

The report recommends protecting networks from compromised machines by segmenting the network and implementing strong authentication to prevent hackers from going from phishing to full-scale reconnaissance of the bank's network.

Hackers are getting faster at break-ins; responders are much slower. The time it takes hackers to break in to a company network keeps dropping — in 2015, 84% of the time it was days or less. Less than 25% of breaches were caught within days.

"On average there could be a six or seven-month gap between the time to compromise and time to discover for a lot of victims," Novak said. "That's a big problem. The threat actors are collaborating and sharing information. They're buying, selling and creating tools, techniques and procedures, selling credentials, sharing information about vulnerable apps."

Victims are not as good at sharing information and collaborating. "The financial services sector is by far the best, but it's all relative," Novak said.

The Financial Services Information Sharing and Analysis Center, the top threat sharing group in banking, has thousands of bank members.

"The challenge I often find is lots of organizations participate in order to collect information," Novak said. "But a lot of organizations struggle with contributing."

Speed of threat data sharing is also critical. Many organizations that suffer massive breaches will only talk about it a year or two later, after all the litigation has been settled. By that time, intel that would have protected others from being victimized has probably gone a little stale.

Companies' internal fraud detection methods have become a lagging indicator. In 2005, 80% of breaches were discovered through internal fraud detection. In 2015, less than one in five were caught that way, but the number of breaches caught by law enforcement and third parties has grown.

"Law enforcement has gotten better and more aware. It's put more resources toward cybersecurity investigations, detection, and litigation," Novak said. "The FBI, the Secret Service and other agencies have all stepped up their game significantly."

Hackers are successfully exploiting old vulnerabilities. Some of the most successful hacks are exploiting vulnerabilities discovered in 2007.

"In financial institutions, we see a lot of cybercriminals taking advantage of well-known older vulnerabilities," Novak said. Having one computer on the network with a five-year-old vulnerability that someone forgot to fix puts an organization at risk.

Insider fraud is down. In financial services, insider privilege misuse accounted for only 3% of security incidents. "Because of a lot of regulation, there's generally a higher degree of background checks, auditing of logging, compliance, that drive a lot of validation of what people are doing and should be doing" in banks, Novak said. People who work in banks know they're being closely monitored, which is a deterrent in and of itself, like a security camera in a store, he said.

Novak noted that banks need to prioritize their security efforts according to the likelihood of an attack happening.

"The approach of security by boiling the ocean is not going to work," he said. "A lot of organizations try to tackle stuff that makes the biggest headlines. Often the stuff that makes the headlines is not the most common stuff that happens [but] it's the most elaborate, exotic stuff that's interesting to talk about."

In an earlier data breach case study report Verizon published, what got the most attention was a story about pirates overtaking ships on the ocean. "That blew our mind – 85% of activity about the report was around the pirate story," Novak said. "The rest of the stuff happened thousands of times to everybody all over the world. But everyone wanted to talk about the pirate attack."

Who could blame them? Pirates are way more fun than web-app-mutilating malware. But the wise path is to focus banks' cybersecurity resources in the areas where they'll make a difference.

Editor at Large Penny Crosman welcomes feedback at