For bankers, there are scary parallels between the IRS' failure to protect sensitive personal information and their own such struggles.

There's the need to accommodate a wide range of users ranging from tech-savvy to tech-avoiding. The use of static data to verify identity. The need to cope with slow-moving bureaucracy. The well-intentioned efforts to improve security that only open new doors for clever hackers.

So while it's tempting to roll your eyes and crack jokes when a government agency slips up, the IRS breach may hold some useful lessons for the financial services industry.

-

With tighter security in the online and mobile channels, fraudsters are turning their attention to vulnerable contact centers, conning eager-to-please phone service reps into coughing up customer information or letting them reset passwords on other peoples accounts.

March 1 -

The FBI's fight with Apple over access to a locked iPhone could undermine software security for financial institutions and their technology vendors and make it harder for banks to do business internationally or use cloud computing.

February 25 -

WASHINGTON The Department of Homeland Security and the Department of Justice on Tuesday released guidelines for the implementation of the Cybersecurity Information Sharing Act, prompting some industry skepticism as well as renewed privacy concerns.

February 16

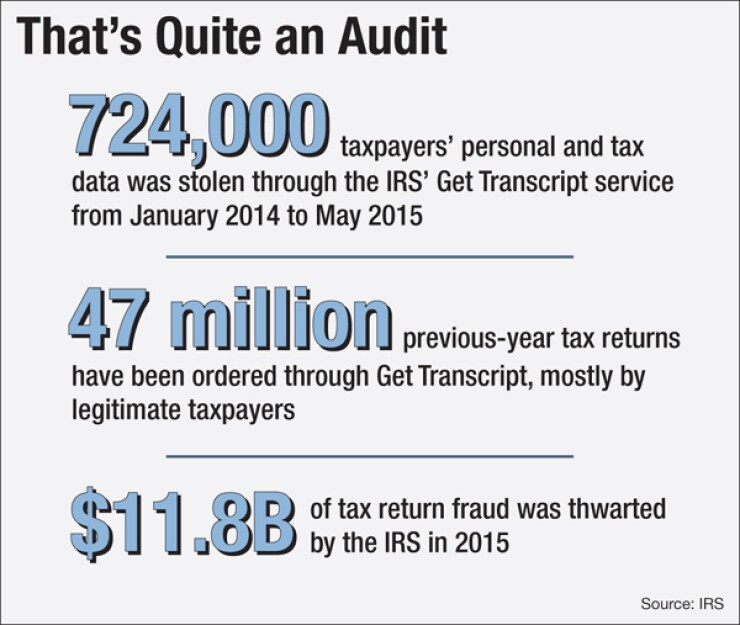

The tax agency acknowledged recently that the number of taxpayers whose information has been stolen by hackers through its systems is 724,000 — more than double the agency's previous estimate. And reports say some of the same taxpayers are getting targeted twice, through the very mechanism set up to protect them.

How the Breaches Happened

Cyberthieves broke in through the IRS's Get Transcript program, which taxpayers use to obtain copies of their federal income tax returns from previous years. Often people need to provide an old tax return when applying for a mortgage or seeking tuition aid, or starting with a new accountant. (The IRS suspended Get Transcript online in May 2015 and is working to restore it with enhanced security.)

To check the identity of the person applying for a tax return, Get Transcript asked for the applicant's name, date of birth, Social Security number and filing status. After that data was provided, the IRS asked four knowledge-based authentication questions.

"The problem is that, in many instances, this information can be gathered by a diligent hacker from public databases, social media where people provide this information, and [from] data breaches," said Steven Weisman, a professor at Bentley University in Waltham, Mass. who has written several books about identity theft and scams.

Some of the stolen data was used to file fraudulent tax returns in the victims' names. The IRS said in May that it had paid more than $50 million to criminals filing fake tax returns. The number of acknowledged victims has doubled since then; logically, the losses must have grown also, although the agency has not shared new numbers. (The IRS did not respond to requests for an interview by deadline.)

The targeted taxpayer doesn't lose money — once she re-proves her identity she can file her return and receive a full refund. But she'll have to wait — it takes an average of 278 days for the IRS to investigate income tax identity theft and return a refund to the correct taxpayer. The ultimate victims are all of us taxpayers who gradually refill the IRS's coffers.

To compound the problem, some of the original victims have been scammed again. To protect victims of income tax identity theft, the IRS began letting them set up a six-digit Identity Protection PIN when filing their returns.

However, the Identity Protection PIN program is protected by that same knowledge-based authentication that hackers broke into in the first place.

The IRS shut down its Identity Protection PIN program on Tuesday and said it's looking to improve security.

To make matters worse, hackers have latched onto this situation and unleashed phishing campaigns targeting taxpayers who may be confused. (More on this in my next post.)

Milan Patel, who until May was the FBI's cyber division chief technology officer, said the IRS is doing its best.

"They're a quite capable organization," said Patel, who is now managing director of the cyberdefense practice at K2 Intelligence. "The challenge is that you have a lot of data, you have a lot of people in the organization who are not cybersecurity experts. How do you educate tens of thousands of people whose main job is to check finances and not worry about cybersecurity?"

He also points out that the IRS has to deal with people all over the country with a wide range in degree of computer literacy.

"They have to balance accessibility with changing technology such that they don't alienate a huge population of the United States that's not tech-savvy," Patel said. "If my father was doing something with his taxes, he would probably call. If he tried to interact with a website with two-factor authentication, he'd be lost."

There are a few takeaways for banks from this mess.

1. Rethink knowledge-based authentication.

Because so much personal data can be found on the Internet, identity thieves sometimes can answer questions better than their victims can.

"This is one of the unintended byproducts of the oversharing economy," said Al Raymond, specialist leader for privacy and data protection at Deloitte (until recently, he was senior vice president and head of privacy and social media compliance at TD Bank). "By putting out so much information about ourselves in social media, fraudsters can easily piece enough of our lives together" to commit fraud of all kinds.

2. Don't let bureaucracy kill a good security idea.

In a report issued last year, the U.S. General Accounting Office reported that the year before, the IRS wanted to be able to compare W-2s to tax returns before issuing refunds. "While there is no 'silver bullet' for combating [identity theft] refund fraud, IRS officials told us that pre-refund W-2 matching could prevent billions of dollars in estimated [identity theft] refund fraud," the GAO said.

Sounds like a no-brainer. But the GAO said this would be too expensive and nixed the idea. It insisted the IRS do a study on the costs before undertaking this change.

"The fact that employers file W-2s with the Social Security Administration, which does not get around to sending them to the IRS until July, at which time the IRS starts matching the employer-sent W-2s with those sent by taxpayers, including identity thieves sending counterfeit W-2s long after refunds have been sent, is absolutely ludicrous," Weisman said.

Yet banks sometimes face similar budget and resource dilemmas.

"Everything is a risk management decision in one way or another," Raymond said. "Banks have thresholds of fraud that are acceptable and they will live with those numbers because it's not worth the effort to get down to a level of 0% fraud."

3. Teach customers to protect their Social Security numbers and other personally identifiable data.

"For bankers, this is a tremendous opportunity to educate your clients, to provide them with information, maybe even seminars, to alert them to best practices they can take," Weisman said. They should explain, for instance, that the Social Security number is the key to identity theft.

Weisman recently went to the eye doctor and was asked for his Social Security number. "They don't need it," he said. He offered his driver's license instead, and the doctor's office was fine with that. "You teach people about limiting those things."

4. Try stronger authentication technology.

The IRS is exploring ideas for preventing identity theft. One is to track device identification numbers to determine when multiple returns are filed from the same device, a possible indicator of fraud.

Similarly, "I think financial institutions should not shy away from the more assertive authentication procedures," Raymond said. Banks can point out that the extra layer of authentication is for the customer's safety and peace of mind, he noted. "I kind of enjoy getting a text from my credit card company asking me if I just bought a big-screen TV in Romania," he said. "I usually didn't."

Weisman said this is an argument for better systems such as dual-factor authentication in which a code is sent to the user's smartphone when she needs to access an account.

Data security is an ongoing battle for all organizations, with hackers typically a step ahead of IT departments. Banks have an advantage in that they can, in theory at least, implement new security technology and procedures faster than a large government agency can.

Editor at Large Penny Crosman welcomes feedback at