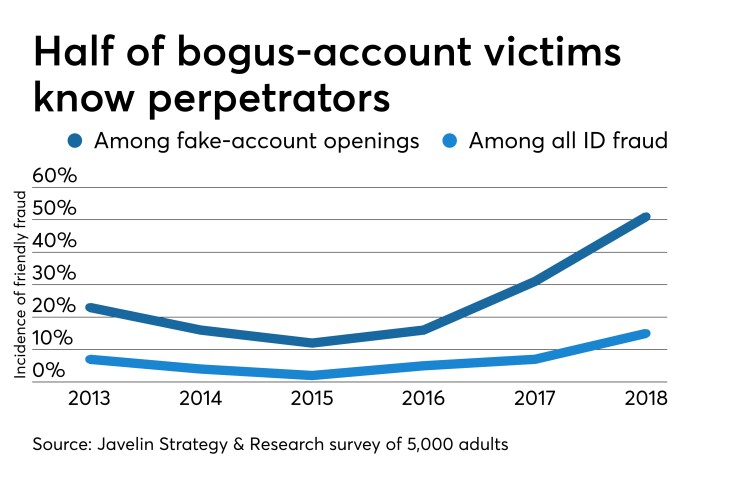

Friendly fraud — when a fraud victim knows the perpetrator, and the fraudster has intimate knowledge of the target — has by all accounts been growing even as overall fraud has decreased in the past year.

According to a study from Javelin Strategy & Research, friendly fraud doubled in 2018, from 7% to 15% of all fraud victims. All told, 14.4 million Americans were fraud victims in 2018.

Merchants are complaining that it is "a very real problem," said Johan Gerber, executive vice president for security and decision products at Mastercard. “As device-based commerce and digital commerce continues to explode, they do see that trend growing rapidly.”

What's especially puzzling is that the problem, often a crime of desperation, has worsened during relatively good economic times. Normally, friendly fraud moves in the opposite direction of the economy, said Al Pascual, senior vice president of research and head of fraud and security at Javelin.

“As the economy starts to turn [down], we see cases increase,” he said.

Critics say banks and card issuers are complicit in the problem, because when customers dispute transactions, they find it easier to allow a chargeback to the merchant than to investigate.

'Fraud' not always apt

A lot of what’s called friendly fraud isn’t fraud at all. Incidents often stem from a lack of communication — a spouse uses a credit card without telling the cardholder, for instance, so when the cardholder gets the bill, the charge looks like fraud. Or children use their parents’ account tied to an Xbox or a Sony PlayStation to buy games without telling their parents. In the latter case, parents could have set controls on who can make purchases on the account.

“But most parents, me included, don’t want to deal with that hassle, so instead you give your child the password and tell them to spend no more than a certain amount,” Monica Eaton-Cardone, co-founder of Chargebacks911, a risk mitigation and chargeback management firm. “You decide to trust him.”

Sometimes cardholders get their credit card bills and simply do not recognize their own charges — perhaps the merchant description does not match the name of the store where a purchase was made, or several purchases were lumped together into one charge, so that the amount seems unfamiliar.

Eaton-Cardone says such misunderstandings account for 57.6% of total friendly fraud chargebacks, which increased 41% in the past two years.

There is also intentional fraud, in which people buy things with their own account or the account of someone they know and refuse to pay for them.

Nordstrom has reported in the past that customers were buying products online from the retailer, receiving the products, calling their bank and claiming that they never received them, and then selling them on eBay.

“They got the chargeback because the customer is aware of this loophole and there's no consequence anywhere,” Eaton-Cardone said. “If I wanted to be dishonest, I could set up an entire business buying Dyson vacuum cleaners and expensive handbags and filing chargebacks on every single one. I wouldn’t have to pay any money and I would never go to jail.”

Where banks fall short

Eaton-Cardone says banks and their regulators are complicit in friendly fraud.

“There are regulations, guidelines and rules in place to protect cardholders, buyers and sellers and give everybody certain responsibilities and rights,” she said. “As a cardholder, if I have a Visa credit card, then I’m responsible for protecting my password, not giving anyone my PIN code, [and] making sure that if I see fraud, I report it. And if I gave my PIN and card to someone and they made charges, then I’m responsible for that, even if that person wasn’t me, because I authorized it.”

If a family member uses a card, by default it’s an authorized charge because it was used by an authorized user, she said.

When customers call their banks to dispute charges, the banks should question the customers and try to determine whether the charges are valid.

If a child bought video games without her parents’ knowledge, for instance, the bank should say, “Your child got the game that she ordered and you have a problem with your child, not with PlayStation,” Eaton-Cardone said. “The credit card company doesn’t say that. When I call and say I have these $500 in charges, I don’t know what they’re for, it’s not fair. My credit card company says OK, no worries, we’ll process a chargeback, tomorrow you’ll see a refund for $500. We’ve built our entire world based on the customer is always right.”

The merchant is not present when the customer calls and does not have little influence in the process, she said. The bank may tell the merchant it is free to dispute the charge, but merchants have little time for this and the window of time in which they can register a complaint have shrunk. In some cases, merchants that used to have 30 days to file a chargeback dispute now have only a few days under current Visa and Mastercard rules.

“When a chargeback is filed, merchants are guilty until proven innocent,” Eaton-Cardone said.

She would like to see collaboration among card issuers.

”If I am a habitual friendly fraudster, I may have 12 different credit cards,” she said. “None of those credit cards see each other. So Capital One is never going to be suspicious that I'm filing so many chargebacks. They're just going to think, she must live next to a neighbor that steals her packages.”

Card issuers’ efforts

Gerber at Mastercard said card issuers try to resist friendly fraud.

“All the card issuers I’ve spoken to find this to be a real problem and are trying to find a solution,” he said.

Card issuers often feel they lack the evidence to dispute chargebacks, Gerber said.

“All they have is what’s on the statement and what the cardholder says to them,” he said. “They also don’t want to find themselves in the middle of a fight between the cardholder and the merchant. The issuers feel they are in a difficult spot in the middle.”

Some have tried to find ways to challenge consumers, but that creates friction for consumers who are genuinely reporting fraud.

“They are between a rock and a hard place because they try to maintain a good relationship with the cardholder, and without real strong data it’s hard for them to decide which transactions to push back on when the consumer says it’s not theirs, versus giving them that easy experience,” Gerber said.

Last week, Mastercard agreed to buy a company called Ethoca to help card issuers and merchants get a better grip on friendly fraud. Ethoca’s Eliminator technology provides visibility into chargeback disputes. It shows the consumer details about a transaction, such as the name of the merchant, the device from which the transaction originated and itemized purchases.

“We want to provide greater transparency to the consumer through this,” said Gerber. “We talk about friendly fraud, which obviously is a big problem, but a lot of that is purely consumer confusion.”

He recently received a credit card bill that included a purchase his wife had made, but neither of them recognized the description. “These things do happen, and that transparency is a big part of getting [friendly fraud] out of the system.”

In trials, Ethoca has found that 25% to 40% of the time, when customers are presented with this information, they recognize the transaction and back off.

Mastercard would like to add the authentication mechanism that was used when somebody bought something online. That way, the customer could be shown the authentication used (say, face ID) and the name of the device on which the transaction occurred, as well as the items in the shopping cart.

“Maybe when you put that all together, it will really help the consumer to understand or remember what happened,” Gerber said. “Or if there is someone trying to game the system, that level of detail should help them to do a double take before they proceed with the chargeback.”

Visa has built technology similar to Ethoca's. “Friendly fraud is a concern for both issuers and merchants, and we have been working with our clients to direct more effort to addressing it," a spokeswoman said.

Visa created a capability for issuers and merchants to exchange additional data about transactions so that issuer customer service staffers can better respond to cardholder questions.

"In many cases, consumers just don’t recognize valid transactions when they see them on their statements, otherwise known as ‘do not recognize’ claims," the spokeswoman said. "We are also equipping merchants with benchmarking and data analysis to identify opportunities to improve fraud performance.”

In a separate example, Synchrony Financial is using artificial intelligence to better detect friendly and other types of fraud. This helps reduce the tension that builds up in grilling customers when they say they a transaction is not theirs.

“Let’s say you don't recognize a transaction on your credit card and you say you weren’t at a Stop & Shop in California last Tuesday,” said Michael Bopp, executive vice president. “You call up customer service and say that. They say, OK, tell us some more. Where were you last Tuesday? How do you know it wasn't your transaction? Do you have any siblings or family members in California? You go through this terribly manual and customer-unfriendly process to confirm the truth of what this person is telling you.”

The reason the call center people are tough is that they do see fraud committed by people who are not who they say they are, or who make a transaction and are trying to avoid paying for it.

Synchrony’s data scientists built a machine-learning model that looks for many other possible clues: the customer’s transaction patterns, the locations of the transactions and transaction patterns of other accounts the customer might have with Synchrony. The model has been trained by the results of past fraud investigations. More than 90% of the time it can confidently determine whether a transaction was the customer’s or truly fraudulent, Bopp said.

FIS is working on a federated digital identity system that banks and card issuers could share to better vet transactions, according to Eric Kraus, vice president of fraud management.

“Nothing is 100% foolproof, but we’re bullish on the use of digital identity and a different approach to authentication, whether you’re talking about an actual consumer interaction or applying for loans and credit lines,” Kraus said. The use of biometrics could make transactions relatively smooth while locking out unauthorized use of an identity or card.

Pascual says the industry has “woken up” to the need to prevent friendly fraud.

“It’s not just, can we save on these losses,” he said. “It’s not just, can I do the customer a service by stopping things before they get out of hand. There are also operational savings that can be realized if you manage this effectively with good information sharing. So I think there’s a lot of incentive in the system for them to work together and be collaborative. I think over time it’s going to get better.”

Editor at Large Penny Crosman welcomes feedback at