Nobody knows when big banks will start raising dividends, but industry watchers say one thing is pretty certain: It could take years for quarterly payouts to reach pre-recession levels.

Some doubt that they ever will again.

"Dividends will slowly ratchet up — but I'm not sure they will return to the sorts of dividend yields that we saw in the past," said Mark Fitzgibbon, a principal and director of research at Sandler O'Neill & Partners LP. "I think investors would prefer if companies utilized excess capital to acquire troubled [or] failed banks. It's a more attractive, I should say, use of that excess capital."

Robust bank dividends were a casualty of the credit crisis. Since 2008, all but a few large banks slashed their quarterly dividends — often to a penny or nickel per share — to conserve cash as loan losses mounted. Before, it was not uncommon for large banks to pay out 30 cents to 50 cents per share.

With the economy on the mend and loan problems easing, healthier institutions like JPMorgan Chase & Co. and U.S. Bancorp have started talking about raising their quarterly payouts, which are 5 cents per share each. The top executives at both companies have said they earn enough money to sustain a higher dividend but don't want to raise it until they have more certainty about where the economy and regulatory reform are headed. Regulators may not bless banks raising their dividends until the end of this year or later.

Whenever dividends start rising, market watchers say, they will probably be much more modest than before the economy collapsed and may stay that way for a while.

Fitzgibbon, for one, estimated that industry's average dividend payout ratio — or the percentage of earnings paid to shareholders — will hover at 30% to 35% after the economy fully recovers. The ratio averaged 40% to 45% before the recession.

Market watchers cite a number of reasons for lower dividends.

Simple math is one. Most large banks issued lots of common stock to raise capital in the last year or so. With more shares outstanding, even if a bank returned to pre-crisis amounts, the dividend per share would be lower. So a bank seeking to return capital to shareholders may first favor a stock buyback.

Another is the makeup of bank investors today.

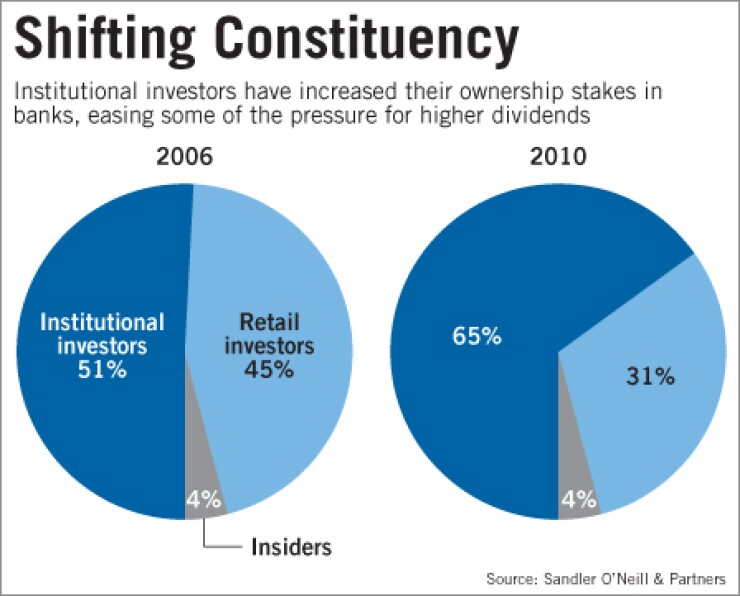

The recession scared off a lot of retail investors from banks. Retirees who parked savings in bank stocks to get the dividend income pulled away as hedge funds and other institutions bought in to the sector.

Retail investors owned 31% of the banking industry as of this year, down from 45% in 2006, according to SNL Financial. Institutional ownership rose to 65%, from 51% during that period.

Charlie Bobrinskoy, vice chairman and director of research at Ariel Investments LLC in Chicago, said the change in banks' investor bases could have strategic and financial consequences. For one thing, hedge funds and other investors are looking to book a return by buying low and selling high. They don't care as much about the dividend, so they won't be clamoring for management to raise it.

They would much prefer that the companies they own hold on to their capital and reinvest it in deals, loan growth or new products that will boost share prices.

"They lost … investors who were looking for safe yield, safe income," Bobrinskoy said. "Now their new class of investor is someone who is much more comfortable with volatility."

Bobrinskoy said bank dividends will certainly rise from their paltry levels. For instance, analysts contacted by Bloomberg expected JPMorgan Chase to increase its quarterly dividend to 25 cents per share this year. They forecast U.S. Bancorp's would rise to 10 cents.

When dividends do go up, Bobrinskoy said, the increase will be intended to signal strength to the market, not so much to reward investors.

Not all observers are convinced the recession has spelled the end of healthy bank dividends.

Greg Donaldson, founder of Donaldson Capital Management LLC, a money manager in Evansville, Ind., said investors speculated that bank dividends would never rebound after the recession of 1991. Investors made a similar claim about utilities several years ago when they fell on hard times.

They were wrong both times, he said. Banks paid big dividends because they generate a lot of free cash. They will have a lot of extra capital in coming years as reserves fall. As that happens, he said, retail investors will come back.

"My view is that you are going to go back to a more rational, slower-growth, less-risky environment, and that was a pretty good time," Donaldson said. "Four or five years ago, a lot of the big utilities got into trouble and slashed their dividends. People are right back buying utilities, and utilities are right back paying dividends. Banks, in a way, are utilities. Now they are gong to be regulated like utilities."