-

USAA has partnered with Coinbase to let users view their bitcoin wallet balances, an added financial management tool indicative of a kind of bundling of non-bank financial services it hopes will differentiate it from its competitors.

November 4 -

General Electric plans to ask early next year for relief from heightened regulatory scrutiny, while its former credit card arm says that it won't be subject to the same stress-testing rules as most banks its size.

October 16 -

No bank has fully disclosed what it spends on the Federal Reserve's Comprehensive Capital Analysis and Review, in part because the figure is hard to isolate. It's a key piece of information missing in the debate over banks' regulatory burden.

May 18

For those banks that feel their grip, the Federal Reserve's supervisory stress tests are tremendously costly.

Citigroup spent $180 million on the annual process — called the Comprehensive Capital Analysis and Review, or CCAR — in just the last six months of 2014. Bank of America announced a shake-up in its leadership ranks after having to resubmit its plan earlier this year; the do-over cost the Charlotte, N.C., company an additional $100 million on top of an undisclosed amount it had already spent.

The rigorous exercise, which was born out of the financial crisis, is designed to judge whether banks will be able to withstand future economic turmoil. Because the stress tests are run only on banking firms with at least $50 billion in assets, bankers have been carefully weighing when and how to pass that cutoff.

There is one large U.S. banking company, though, that does not need to stress out over the Fed's stress tests: United Services Automobile Association in San Antonio.

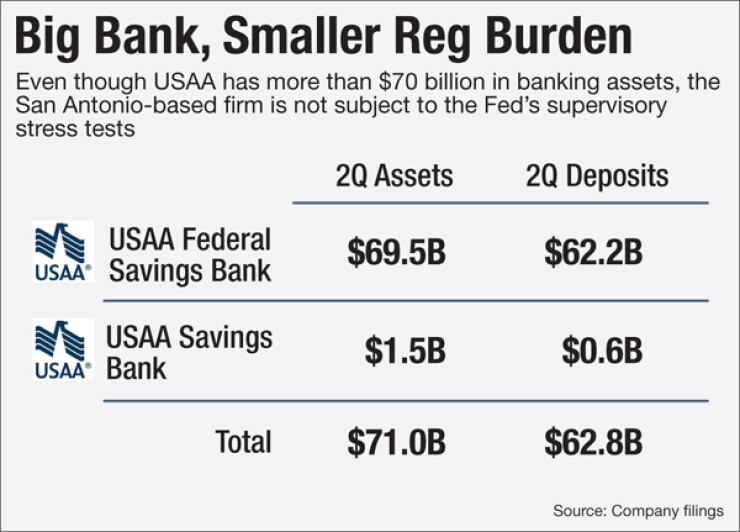

USAA, which has $134.2 billion in total assets, has carved out a niche by providing financial products to members of the military and their families. Assets at its USAA Federal Savings Bank unit have more than doubled over the last six and a half years. They currently sit at $69.5 billion.

But crucially from a regulatory standpoint, USAA is organized as a savings and loan holding company, rather than a bank holding company. Even more fortuitously, the firm is the only savings and loan holding company with more than $50 billion in banking assets that qualifies for a little-noticed loophole established by the Fed in 2013.

Consequently, USAA is not subject to the Fed's supervisory stress tests, and unlike other large savings and loan holding companies, it is not even required to report its regulatory capital to the government.

"While savings and loan holding companies are not subject to the CCAR program, we're ready to abide by any new or revised regulation," said USAA spokesman Roger Wildermuth.

The company's leg up is the residue of a jury-rigged regulatory system, built layer upon layer over several decades, to the point where no one can offer a rational explanation for it.

"It makes no sense," said Lawrence Mielnicki, an industry consultant at RiskGroup360. "If stress-testing is validly a part of a strong risk management system, it makes no sense to exclude any class of financial institution."

Loopholes Live On

For several decades after the Great Depression, S&Ls were subject to tight restrictions on the products they could offer. Savings accounts were allowed, as were mortgage loans. But it was not until the 1970s that savings and loans were even allowed to let their depositors write checks on their savings accounts.

In the years that followed, S&Ls came to look much more like banks. They got the authority to issue credit cards, and to invest more widely in consumer and commercial loans.

But thrifts lobbied to retain various regulatory advantages even after the financial shock they caused in the late 1980s. And in the years leading up to the more recent financial crisis, savings and loan holding companies still were not subject to formal capital requirements.

Prior to 2008, the thrift charter was widely regarded as a ticket to light-touch regulation. Companies that later became symbols of the subprime mortgage bubble's excesses, including Countrywide Financial and Washington Mutual, were supervised by the Office of Thrift Supervision.

So was American International Group, a savings and loan holding company whose far-flung operations included a London-based division that would have brought down the company if not for a massive government bailout.

"Despite its systemic importance, supervision of AIG at the holding company level was essentially nonexistent," author Thomas Stanton wrote in a 2012 book.

The Dodd-Frank Act was supposed to eliminate the regulatory advantages that came with the thrift charter.

The 2010 law shut down the OTS entirely. And it included an amendment authored by Sen. Susan Collins, R-Maine, which ordered regulators to establish minimum capital requirements for thrift holding companies that would be at least as stringent as those for bank holding companies.

But when the time came to implement that part of Dodd-Frank, the Fed decided to divide thrift holding companies into two separate categories. One group was made subject to the new capital rules. The second group argued for — and got — an exemption.

For the first set of firms, the capital rules took effect on Jan. 1, 2015. This group includes Charles Schwab Corp., a thrift holding company with $122.4 billion in banking assets. Schwab began reporting its regulatory capital in the first quarter of this year.

Schwab is not yet subject to CCAR, which is currently reserved for bank holding companies. But now that the company has begun reporting its regulatory capital, observers expect that the company will eventually get swept into the Fed's supervisory stress-test regime. The Fed does not subject large firms to CCAR until their capital rules have been in place for at least a year.

Synchrony Financial, the credit card issuer that recently spun off from General Electric and got the Fed's approval to become a stand-alone thrift holding company, appears to be in a similar boat. Chief Financial Officer Brian Doubles said during a conference call last month that Synchrony plans to file a capital plan with the Fed, even though it is not subject to CCAR. Synchrony did not return a call seeking further clarification.

Benefits of Owning an Insurance Business

The carve-out for the second group of thrift holding companies was based on an elaborate and arcane set of criteria. It boiled down to this: firms that have either substantial insurance operations or substantial nonfinancial businesses do not have to report their regulatory capital to the government.

Some of the firms that qualified for the exemption have small banks tacked onto much larger nonbanking businesses. For example, State Farm Mutual Automobile Insurance Co. has a $139.4 billion in total assets, but its bank has only $16.6 billion in assets. It is primarily an insurance company.

John Deere Capital Corp. has $35.2 billion in total assets, but its bank has just $2.6 billion in assets. It is primarily a manufacturer.

USAA is quite different. It qualified for the Fed's exemption by virtue of its insurance business — which offers auto insurance, life insurance and homeowner insurance — even though more than half of its total assets are in two banking subsidiaries.

USAA offers a wide range of consumer banking products — including checking accounts, savings accounts, credit cards, auto loans, mortgages and personal loans — and competes against any number of big banks with large national advertising budgets.

While the company does not have an extensive branch network, it has emerged as one of the industry's leaders in digital banking.

In an email, the USAA spokesman said the company is highly regulated, and noted that USAA conducts company-run stress tests for capital adequacy. Those stress tests, required by Dodd-Frank for banking companies with more than $10 billion in assets, are less rigorous than the Fed's supervisory stress tests.

No Firm Deadline

In 2013, when the Fed established the exemption, it stated that it expected to implement a framework for the exempt thrift holding companies by the time the new capital rules took effect. But the new framework has yet to arrive.

"So they're already basically 11 months overdue," said William Stern, a financial industry lawyer at Goodwin Procter.

At a congressional hearing in September, Thomas Sullivan, a senior adviser in the Fed's department of banking supervision and regulation, indicated that the Fed is not in a hurry to finish capital rules for firms that qualified for the 2013 carve-out, or for other insurance companies.

"We are not being driven by [an] artificial time line to develop that standard. Right now, in terms of our progress, we continue solicit views from external parties, continue some degree of internal deliberation, as we prepare to present to the [Fed] board an array of options that could be considered," he testified.

"I don't think this is something we want to hurry or rush along," Sullivan added. "I think this is something we want to be very careful and thoughtful and deliberate about."

A Fed spokesman declined to comment on the cause of the delay, or to say when the Fed expects to finish the rules.

After the passage of Dodd-Frank, the Fed has been trying to bone up on the insurance business, but that process has no end in sight.

"The Federal Reserve is investing significant time and effort into enhancing our understanding of the insurance industry and the firms we supervise. We are committed to tailoring our framework to the specific business lines, risk profiles and systemic footprints of the firms we oversee," Sullivan testified.

A lucky beneficiary is USAA, the 24th largest financial holding company in the U.S. It is just behind Citizens Financial Group, and one spot ahead of Santander Holdings USA.

USAA has more banking assets than Huntington Bancshares, Comerica and Zions Bancorp., all of which were subject to CCAR last year. But for the indefinite future, USAA will not have to bear the costs of participating.

"It's a big task, a big undertaking, and it's quite expensive," said Matthew Anderson, managing director at Trepp LLC and an expert on bank stress-testing. "So it's not something that I think most institutions would undertake unless they were required to do it."