CHARLOTTE — Those who say Six Sigma is not useful for financial services companies often point to the big differences between factories, for which the quality assurance program was developed, and banks, which measure success in a more nuanced way.

But Bank of America Corp. — the biggest U.S. retail banking company — also happens to be one of the banking industry’s biggest proponents of Six Sigma, and it has stepped forward to rebut the skeptics.

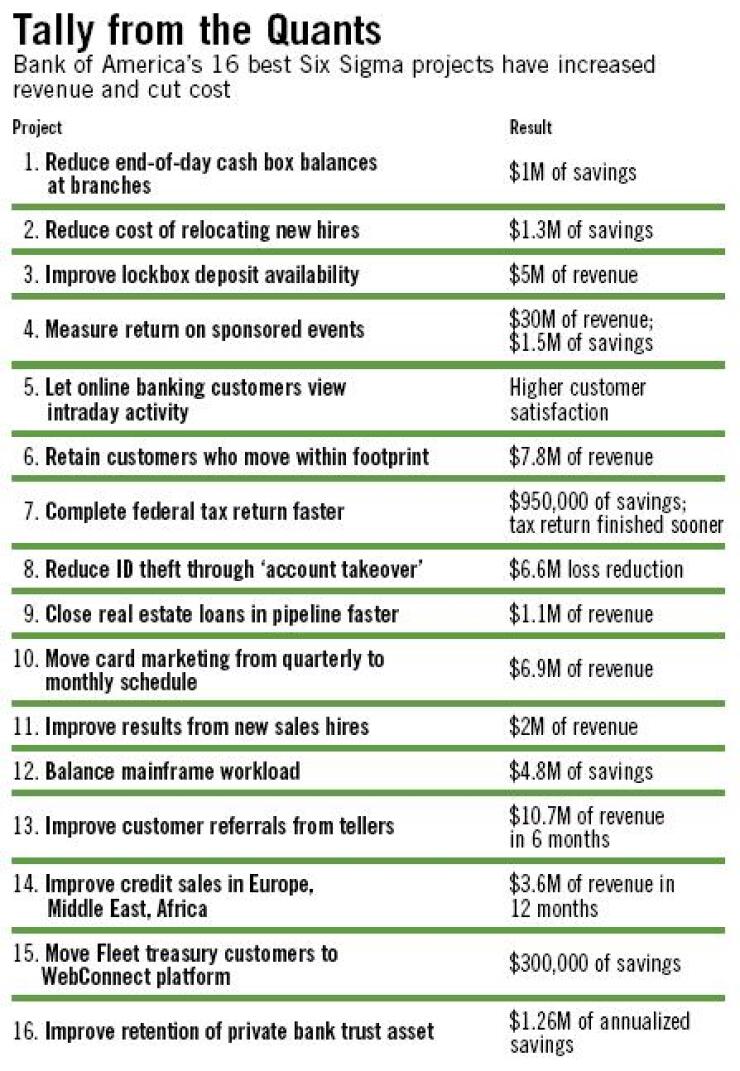

Last year alone Bank of America completed thousands of Six Sigma projects, each taking aim at a specific function. Last week it held an internal expo to showcase the 16 best projects, which produced more than $85 million of revenue and cost savings.

Including the many projects that were not featured at the expo, Six Sigma added more than $2 billion to the bottom line over the last three years, more than half of it in revenue generation.

Some of the projects were large, such as a sports sponsorship review that was purported to have generated $30 million of revenue and saved $1.5 million of costs. Some were more modest, such as an effort to get FleetBoston Financial Corp.’s treasury customers to convert to WebConnect, an Internet-based reporting program. That effort was said to produce $300,000 of savings.

Milton Jones Jr., B of A’s quality and productivity executive, says the Six Sigma process yields measurements that are far from subjective.

“What we’re finding is that by improving our quality of service, customers have fewer problems, and that makes them more loyal to us,” he said. “And that improvement in process, which can be measured, is contributing to that improvement in service.”

How does B of A measure quality of service? How does it assign a value to factors that most people might assume cannot be described through a numerical analysis?

The answer sits in a bookcase behind Mr. Jones’ desk, mixed in among awards, photos, and autographed footballs — a thick brown text, “The Six Sigma Handbook.”

Mr. Jones describes B of A’s business practices as a series of steps that can be broken down into distinct, manageable chunks and studied using the Six Sigma statistical analysis tools.

“We want to find the best way” to do something “and then make sure it’s done that way every time,” he said.

Mr. Jones was one of the judges of the second annual “Best of Six Sigma Expo.” He said he was looking not just for an overall contribution to the bottom line, but also for creativity and a rigorous analysis of available data. He said the event was aimed at inspiring other employees and providing them with ideas for using Six Sigma tools in new ways.

For example, one project verified, and measured, what many people might have suspected but probably could not prove — that treating good customers to food and wine can pay off.

B of A organized swank parties at PGA golf tournaments in several cities last year and invited some local customers. All the 700 invited guests were people whom business managers and salespeople had identified as already generating a lot of revenue, but capable of generating more. A control group of customers who fit the same profile was not invited.

In 12 months following the events, sales from the control group had risen, but sales from the customers who had been invited to the parties rose by $30 million more than the lift in the control group. Even customers who had been invited but had not attended had contributed bigger revenue increases than the customers who had been excluded.

Vele Galovski, a B of A senior vice president for customer satisfaction and loyalty, said the key to making Six Sigma work is in defining the exact problem, because once you can explain exactly what you want to study, you can measure it.

“This has given us a disciplined look at what we’re here for: to satisfy the customer,” he said.

And according to B of A’s surveys, the customers are indeed satisfied. In the last two years, Mr. Jones said, the percentage of people who give it a score of 9 or 10 on a 10-point satisfaction scale has risen from 41% to 52%.

“Most retail banks get customers from referrals,” and the people who give B of A a score of 9 or higher will promote the company to their friends, Mr. Galovski said. Those referrals helped the company get 500,000 net new accounts (excluding acquisitions) in 2002 and another 1.2 million last year, and it expects to get 2 million more this year, he said. “By the end of this year we will have added the equivalent of a top 10 bank, just from organic growth.”

Another project examined customer response to a feature added to the online banking site last year. Responding to focus groups and customer feedback, the online banking team determined that customers want to be able to view intraday transactions on the Web in real time. As highlighted in one television commercial, people want to use their debit cards to buy a cup of coffee, and then see the details of that transaction on a laptop computer by the time they carry the coffee to a table in the cafe.

After that capability was implemented, surveys indicated that customers were pleased. How pleased? Seventy-seven percent of B of A’s online banking customers said they were more satisfied with the bank.

And that increase had a direct effect on the bottom line, even though it may initially seem hard to measure. Using Six Sigma tools, B of A found that adding this feature prompted 24% of its online banking customers to visit the branch less often, 38.5% said they would make fewer calls to the call center, and 45% said they would increase their use of online banking and bill payment features.

The results: a 7% increase in online banking sessions, an 11% reduction in calls from people who use online banking, and total savings of $3.9 million.

Another project determined that B of A was spending well over the industry average for moving newly hired employees from one city to another, mainly because there was no standard process to determine the assistance people could expect, including mover’s fees and rent on temporary housing.

By imposing a companywide moving policy, and avoiding the individual exceptions that were driving up overall expenses, B of A saved $1.3 million.

It was also able to study the costs of losing customers who move to a new region. Customers closed 280,000 accounts last year because they were moving, but only 4% of the customers moved out of B of A’s area of operations. Since the rest had no reason to close their accounts, a program was developed to persuade them not to defect.

This program included asking tellers to find a branch close to a customer’s new home and by making address changes easier. The goal is to retain relationships with half of the customers who move within a state. Fifty-six percent of the accounts closed because of relocation last year belonged to customers who moved within a state, and persuading half of them to stay at B of A would lead to revenue of $62 million over five years.

Denise Valentine, an analyst with the Boston market research firm Celent Communications LLC, said the most successful Six Sigma projects work at this level of detail: examining and improving small processes.

Just as a mechanical engineer on an assembly line can tweak the way a car is put together, a financial services executive can study and improve everything a bank does, she said. “There is a large, cumulative impact of chipping away at small issues and costs in an organization. They just keep adding up.”

Though many financial services firms use Six Sigma, few are as outspoken about it as B of A.

At Wachovia Corp., another Charlotte banking giant, Six Sigma is considered just one tool to do the job, according to Greg Swindell, a senior vice president in the operational services group. As a result, Wachovia uses Six Sigma methods when they seem most appropriate — especially in areas similar to manufacturing — and will use other productivity tools when they seem like the best fit.

For example, one recent Six Sigma project studied inbound mail that had to be run through a sorter more than once because of a missing or illegible bar code. After improving the sorting process, the percentage of rejected letters dropped from between 40% and 50% to about 5%, dramatically reducing the amount of human labor required in the mailroom.

But Mr. Swindell said Wachovia employees are using other tools as well. “We are not training everyone to attack everything in the company with Six Sigma. Our approach doesn’t have to use Six Sigma.” It just has to be effective.

Ms. Valentine said B of A is unusual, because its Six Sigma strategy has been mandated from the top.

Ken Lewis, the chief executive officer, announced in 2001 that it would begin implementing Six Sigma techniques throughout the operation. Since then the methodology has permeated the company.

Mr. Jones said the CEO “is very committed to, and supportive of,” the Six Sigma effort. “There are very few companies in the country where the CEO has made such a commitment.”