-

To obtain approval and funding for security improvements, bank technologists have to make their case by pointing to losses from recent security breaches. But calculating those losses can be tricky.

September 11 -

Alabama State Employees Credit Union has filed the first class action lawsuit by a financial services company against Target Corp. over costs from the massive card security data breach the retailer suffered from Black Friday to mid-December.

January 2 -

Within the past 12 months, one large retailer after another has fallen victim to a massive data breach. But at least the pilfered data is getting harder for thieves to monetize.

September 9 -

One of the two banks suing retailer Target and security vendor Trustwave in connection with the retailer's high-profile data breach has backed off.

March 31 -

Green Bank has dropped a lawsuit against Target and security vendor Trustwave that stemmed from the retailer's 2013 data breach.

April 1

Banks are fed up with their losses tied to data breaches at major retailers, but their odds of getting any compensation through the courts are slim.

Lawsuits filed by banks against Target and Home Depot face many hurdles, lawyers say. The main problem is a dearth of laws outlining retailers' responsibilities for keeping data secure a longtime complaint of the banking lobby.

In the absence of clear rules, the lawsuits rely on untested lines of argument.

The first significant ruling on this argument may be coming soon. Judge Paul Magnuson of the U.S. District Court for Minnesota could rule shortly on whether a class action against Target can proceed, and the decision could shape banks' strategy in future cases.

"There's not really the statutory support for the claims, but that doesn't mean there isn't an injury," said Sharon Klein, a Pepper Hamilton partner who specializes in data-security issues. "I think the banks are frankly the biggest losers here, and they're looking for some recourse to recoup their losses."

The Target class action, brought by a group of lenders including Umpqua Bank in Oregon and Mutual Bank in Massachusetts, alleges that the retailers' lax security allowed its systems to be infiltrated last November and December. They claim the breach could end up costing banks and retailers as much as $18 billion.

"Target's completely avoidable data breach inflicted significant financial damage upon plaintiffs who had to act immediately to mitigate present debit and credit card fraud, while simultaneously taking steps to prevent future fraud," said an amended complaint filed last month.

The $3.6 billion-asset First NBC Bank in Louisiana this month became the first lender to sue Home Depot over its breach, using a similar argument.

These suits are mostly uncharted legal territory, and there have been very few definitive rulings in cases like this, lawyers say. Several banks that sued Target earlier this year have already dropped their suits, and similar cases following a data breach at TJ Maxx announced in 2007 were either dropped, dismissed or settled.

In its motion to dismiss the suit, filed Sept. 2., Target said there was only one previous case in which a court ruled in the bank's favor, and that suit was later dismissed.

Representatives of Target, Home Depot, First NBC, Umpqua and some other plaintiffs did not comment on the suits.

While the result is very much up in the air, the suits are facing long odds, observers said.

"The data-securities law that currently exists in the United States is weak," says Al Pascual, director of fraud at Javelin Strategy and Research. "The bar is set very high in these cases, and it's almost impossible to prove that substantial losses are related to the breach."

BLOW TO SMALL BANKS

There's no question that when a big retailer gets hacked, banks pay. They have to reissue cards and reimburse customers for fraudulent transactions, and they

It is tricky to estimate these costs because data is sometimes not used until well after it is stolen, but Pascual said that financial institutions and merchants lost $11 billion in card fraud last year (not just from breaches.)

Beyond the cost of fraudulent transactions, reissuing cards can be expensive. A survey of 535 banks released in July by the American Bankers Association a longtime advocate for tightening data-security requirements for merchants reported that banks had to reissue an average of 8% of their debit cards after the Target breach, at an average cost of nearly $10 per card.

Some of these costs may eventually be reimbursed through the card network. When a merchant fails to follow security measures outlined in the Payment Card Industry Data Security Standards and is hacked, it generally has to pay fines to other network participants.

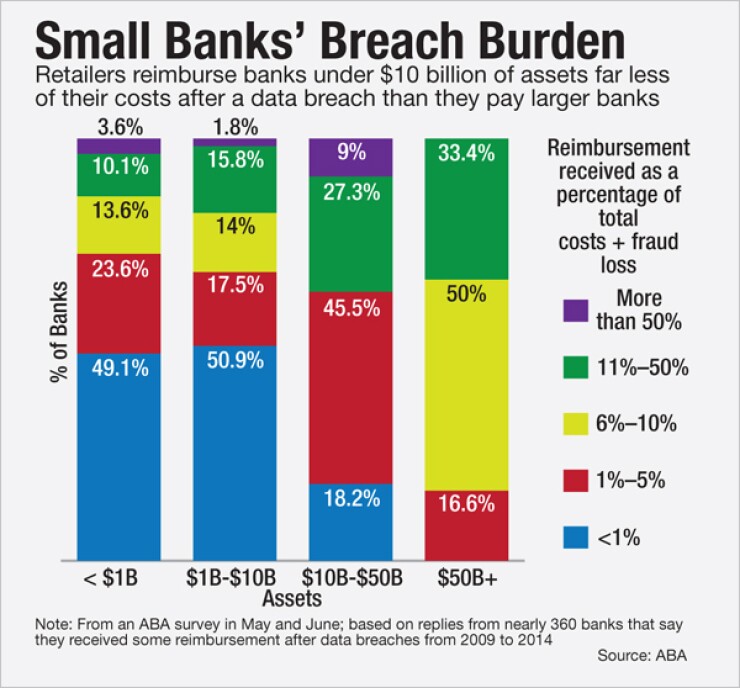

But these payments rarely cover a bank's full losses. In the ABA survey, most banks reported that they were reimbursed for less than 10% of their losses.

Smaller banks are generally hit harder by breaches. Because of economies of scale, it costs more for them to reissue each customer's card. Moreover, they often lack the fraud-alert tools to identify and respond to possible breaches before they are public knowledge.

"Big banks have sophisticated analytics and they know about the breaches well in advance of the announcement. The little banks know when the rest of us do," said Julie Conroy, research director for the Aite Group.

Yet Conroy thinks the big banks are smart to stay out of these class actions and to focus instead on preventing future attacks. "They recognize that [the suits] are futile. Their legal departments have much bigger fish to fry," she said.

The problem is that the companies hacked can easily argue that they are the victims, rather than the cause, of the breach.

"I don't think arguments that Home Depot is negligent with the data are going to hold up," Conroy said. "The fact is that there are very sophisticated thieves trying to breach these systems. They breach banks, too."

LONGTIME FIGHT

For years, there has been a public debate over who bears the blame for these losses, and it has been conducted largely through warring press releases by trade groups representing financial institutions and ones representing merchants.

In June, for instance, the National Association of Convenience Stores claimed financial institutions are largely responsible for the fraud because their longstanding failure to use more secure payment methods like chip-and-PIN cards.

Banks argue that the playing field should be leveled. The Gramm-Leach-Bliley Act holds banks to high standards for data security, they say. No comparable law exists outlining merchants' responsibilities for data security a sore point for the banking industry.

"Banks say, 'We're handling financial data, they're handling financial data, why haven't they been held accountable?'" Pascual said.

Yet banks probably will not be able to recoup their data-breach losses until stronger data-security laws for retailers are enacted.

"Until something changes at the national level, I would put money on the fact that nobody is going to get paid," he said.

'UNTESTED THEORIES'

Until then, the class actions have to rely on "old-school theories of liability," Klein said.

"I hate to say 'creative,' but these are untested theories," Klein said. "That doesn't mean they're not viable, however."

The main thrust of the claims in both the Target and the Home Depot case is that the retailers' negligence permitted the data breaches.

Recent news reports would seem to aid these arguments. Since Home Depot confirmed the cyberattack on Sept. 8, news outlets have reported, based on interviews with former employees of the retailer, that its systems were inadequately guarded. For instance,

Similarly, a report commissioned by a U.S. Senate committee found that Target missed several warnings that its network was breached and failed to segregate its most sensitive information from its other systems.

Still, claims for negligence may be a tough sell in both cases. Courts generally only award claims for negligence in cases where there is a direct relationship between the parties, and it can be tricky to claim that a card issuer and a merchant have such a relationship, lawyers say.

Target made this point in its motion to dismiss the suit, filed Sept. 2. Card-issuing banks and merchants "have no direct dealings with one another in the payment-card transaction process," Target said. Just as an individual has no legal obligation to protect a stranger from harm caused by a third party, Target had no such responsibility to the banks, it argued.

Additionally, contracts between companies using card networks generally specify what happens in cases like this, making it tougher to bring legal action. The Payment Card Industry standards lay out what steps a merchant must take to secure data. But this "is a set of minimum standards, not a silver bullet or a panacea," and it is a long way from failing to comply with these standards to being legally negligent, Conroy said.

Some retailers and banks hold data-breach insurance, but there are still many uncertainties about who holds such coverage and what it covers, said Randy Maniloff, an attorney at White & Williams who specializes in insurance. Plus, "in a major, major breach, no company is going to have adequate coverage," he said.

Even if the Target and Home Depot lawsuits are unsuccessful, they could point the way toward banks' subsequent strategy to reduce the costs of data breaches.

"We need one or two [cases] to get settled soon so there's precedent," Conroy said. "The merchant breaches are not going to go away any time soon."