-

The unprecedented accommodative interest rate environment has spurred banks to offer long-term loans at very low rates of return, and if the cost of funds goes up especially if it goes up more dramatically than expected it could put depository institutions in a tough position.

November 6 -

Fidelity Investments and Federated Investors are walking clients through major changes in the $2.7 trillion money fund business as banks fear another blow to funding.

February 13 -

The Securities and Exchange Commission appears poised to soon finalize a plan to reform the $2.6 trillion money market mutual fund industry.

May 29 -

A response to Boston Fed President Eric Rosengren.

December 12

After years of fighting new money-market rules, the financial services industry is now stuck with them. But for some banks eager to add low-cost deposits to fund loan growth, the changes could actually work in their favor, industry experts say.

The money-market industry has been resisting reform since shortly after the financial crisis, but the overhaul will finally go into effect on Oct. 14, 2016. The rules, meant to prevent a repeat of the money-fund panic of 2008, are widely expected to make the funds less attractive to investors and spur outflows, estimates of which range from manageable to catastrophic for the funds.

Banks that are dependent on money funds for wholesale funding will be hardest hit because that funding would probably become more expensive. Banks that sponsor money funds could lose revenue, or may even have to sell the funds if they can't absorb the cost of the new regulations.

But other banks may find institutional depositors who pulled cash from money funds knocking on their door. With big banks

"For banks that can take substantial sums this will be a great opportunity to chase the public-sector money," said Chris Whalen, an analyst at Kroll Bond Rating Agency. "As certain investors decide they don't want to use money-market funds because of the reforms, it will create an opportunity for small and mid-size banks to grow stable funding."

The Federal Reserve Board's recent decision to start raising interest rates should allow money-market funds to offer more attractive returns, but the reforms could cancel out those gains, giving banks a small advantage in the fight for deposits.

"I think the money fund industry will struggle to compete with yield, simply because of the limitations put on them in what's out there for them to buy," said Bill Demchak, the chief executive of PNC Financial Services Group, at a conference in New York in December.

How aggressive banks are in pursuing deposits flowing out of money funds remains to be seen. Banks are still experiencing sluggish loan growth and have little need for an influx of wholesale deposits, said Roger Merritt, managing director of funds and asset management for Fitch Ratings.

"The counterargument is how much demand do banks really have for wholesale deposits," he said.

The money-fund reforms are intended to prevent a repeat of September 2008, when the failure of the Reserve Fund — the original money-market fund, founded in 1971 — caused investors to frantically pull cash from money funds. The Reserve Fund had heavily invested in Lehman Brothers debt and was unable to maintain its share price when the investment bank failed.

The U.S. government stepped in to guarantee all money-fund assets shortly thereafter, stopping the run. Many large banks also had to spend heavily to prop up their money funds' share prices and avoid "breaking the buck," the term for when the share price dips below par.

The reforms finally placed by the Securities and Exchange Commission in 2014 were bitterly opposed by fund industry titans like Vanguard and Fidelity.

The new rules would allow the value of some money-market funds to "float," rather than be fixed at par. That could hurt their main attraction, of being seen as an ultrasafe cash alternative. The reforms also let funds stop investors from withdrawing their money or charge fees to do so during times of market turmoil.

Estimates of reform-related outflows from money funds have varied widely, from single digits to more than 60%, but with the implementation date closing in it appears that outflows will be on the lower side.

"So far we haven't seen much in terms of investor flows," said Fitch's Merritt.

In a global survey of institutional investors released in November by J.P. Morgan, 83% of respondents said they would maintain or increase their money-market investments. The impact should be greater on prime money-market funds, which invest in corporate debt and would feel the brunt of the new reforms. Just 70% of investors said they intend to still use these funds after reforms go into effect.

Banks that sponsor money funds should have "a negative, albeit modest, revenue effect" due to the outflows and are likely to spur money-fund consolidation, a group of Moody's analysts wrote shortly after the new rules were announced.

In the years since interest rates have gone to zero, sponsoring money funds has been an unprofitable business, and the new regulations could be the last straw for some.

Bank of America, for instance, agreed to sell its $87 billion money-fund business to BlackRock in November. The bank had been "supplementing that business for years" before deciding to sell, CEO Brian Moynihan said last month at a conference.

"For anyone who's in this business it's been a very difficult seven or eight years, where they've had to forgo a tremendous amount of revenue to maintain a presence, and the cost of implementing a reform are an additional headwind," said Merritt.

Banks that rely on such funds for financing could face a modest cash crunch, but the effect will be "manageable" because "[m]oney funds comprise only a moderate level of overall bank funding," Fitch analysts wrote earlier this year. Foreign banks without substantial U.S.-dollar retail presence rely more heavily on money funds for financing, and could feel the pinch more acutely.

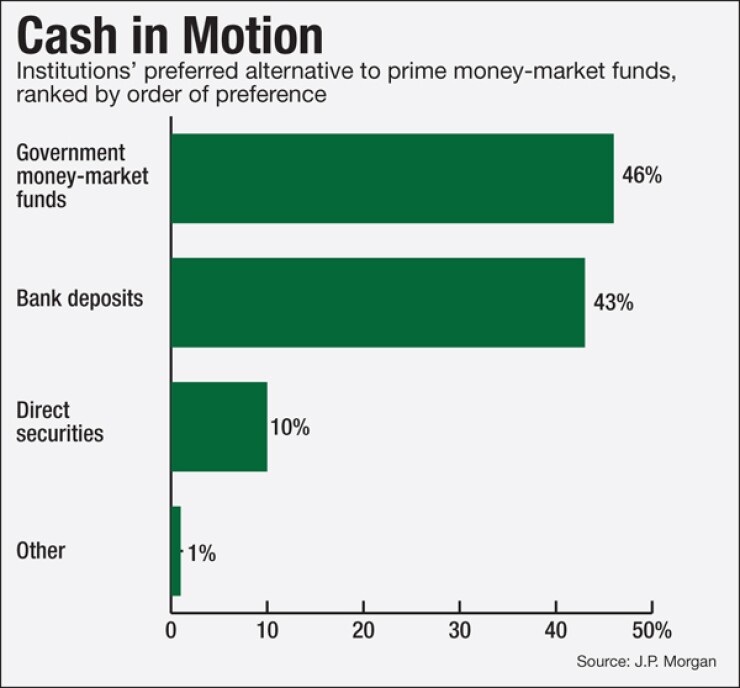

Banks that use the funds to manage their cash will also face a choice of whether to put up with the new rules or pull their investments. Some prime money-market funds have started preemptively converting to so-called government money-market funds only as a way of avoiding the reforms, which apply to funds that invest in corporate but not government debt. Of those likely to pull money out of prime money-market funds, 46% of respondents said they would most likely shift to government money-market funds while 43% said they were most apt to park funds in banks, according to the J.P. Morgan survey.

However, government funds have typically offered yields about 12 basis points lower than prime funds, said Greg Fayvilevich, a director at Fitch Ratings.

"Right now, with returns very compressed, the difference is not as meaningful," he said. "However, as interest rates rise we may see the spread between the products increase back to historical level, maybe even more."