-

Mixed signals from regulators on everything from electronic checks to Operation Choke Point - only create fear, uncertainty and doubt among those in the business of improving the payment system, writes Glen Fossella.

August 19 -

In a highly unusual initiative, small community bank Independence Bancshares has been building a real-time transactions processing system. CEO Gordon Baird hopes to attract others to use it, too.

April 30 -

Independence Bancshares, (IEBS) in Greenville, S.C., has filed multiple mobile payment patent technology applications with the United States Patent and Trademark Office.

April 4

Banks are aggressively securing new and potentially valuable intellectual properties, a strategy shift that raises questions about how banks fit into the patent system.

Once strangers at the patent office, banks are now rapidly increasing their patent portfolios. Several institutions, led by Bank of America and JPMorgan Chase, have in the past several years been awarded hundreds of patents for new banking and payments technologies, financial products and business techniques.

This surge in patent filings has reversed the banking industry's historic indifference to patenting. Court rulings and legislative changes over the past decade have opened the door for banks to win new patents, and many have rushed to seize the opportunity.

"For many years, financial institutions just didn't know much about patents. Now they've started to realize that they could really benefit from them," said Megan La Belle, a professor at Catholic University of America's Columbus School of Law who last year published with her colleague Heidi Schooner a

It is not yet clear, though, precisely what benefits banks expect to gain. Banks have not yet sued to defend their newly acquired patents, and there is no public information on whether they have been licensing or selling patents. Bank of America and JPMorgan, the two banks most active in the patent system, declined to discuss their patent strategies.

The patent boom has two likely causes, experts say. Big banks are now, in effect, large technology companies, and so it is natural for them to produce more patents. Bank of America's global technology and operations department, for instance, has more than 100,000 employees, spends $3 billion a year on software development and has 2,100 patents,

A tech patent with broad applicability outside of the banking sector say, a method for improving data privacy "could be hugely profitable if your patent rights are broad enough," La Belle said. "Banks have seen how companies like Apple and Samsung have benefited from their patents."

The other main cause is that patents offer long-term protection against lawsuits. Banks have spent huge sums over the last decade fighting so-called patent trolls, a term for patent owners who do not use their intellectual properties but try to extract legal damages or licensing fees by accusing companies of infringement.

A large patent portfolio offers ammunition in patent disputes and can scare off trolls by raising the threat of countersuits.

Banks are building "war chests" of patents to for "defensive purposes," said Mike Connor, the co-chair of the intellectual property practice at Alston & Bird. "They are all aware now of what you can do with a patent because they've been sued," he said.

Times have clearly changed. Banks have long accepted patents as loan collateral Thomas Edison, for instance, founded General Electric with a loan backed by his patent for the lightbulb but only rarely sought patents on their own inventions. Banks generally protected their intellectual property with copyrights, trademarks and trade secrets.

That shifted in 1998, when a federal appeals court ruled that "methods of doing business" a category that includes most financial innovations could be patented. This ruling gave rise to a huge increase over the next decade in the number of patents awarded by the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office.

It also led to a huge increase in dubious patents and patent-troll lawsuits. Ten times as many federal patent suits were filed in 2006 as in 1990. Business groups, particularly the tech and finance sectors, began pressuring Congress to reform the patent system to weed out low-quality patents and reduce patent litigation.

The Financial Services Roundtable and the American Bankers Association were among the groups that lobbied for patent reform, and they

This change has reduced banks' patent-troll headaches substantially, lawyers say. It has also coincided with a steady, dramatic rise in banks' interest in patents over the past five years.

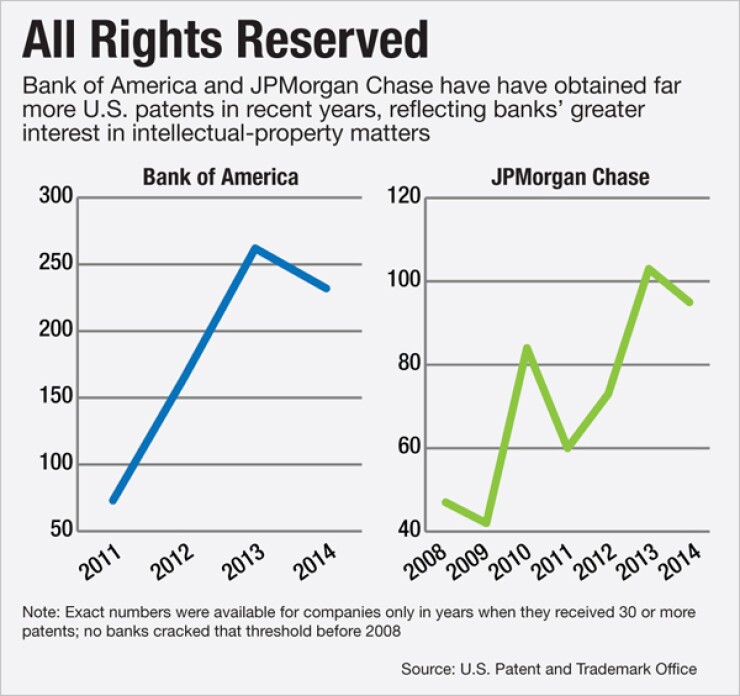

The numbers bear this out. The patent office annually ranks the companies that receive 30 or more patents a year. Tech companies like IBM, Sony, Apple and Samsung generally top the rankings.

But banks have been creeping up. No banks made this list until 2008,when JPMorgan received 47 patents. It has gradually ramped up its efforts, and last year was awarded 95 patents. Goldman Sachs and Morgan Stanley have also made the list in the past five years.

But Bank of America has taken the patenting strategy the furthest. It first appeared on the rankings in 2011, with 73 patents, and last year it received 232 patents, the most of any bank.

That latest total was higher than those of major companies or educational institutions in fields that have traditionally relied on patent protection, like the pharmaceutical companies Roche and Merck, the electronics company Casio, the carmaker Toyota or even Stanford University.

Most of the banks' new patents relate directly to finance. This year, to name a few, JPMorgan has received patents for a type of mobile ATM, a method for automatically sorting customer calls to improve cross-selling, and a new way for automatically matching trading partners.

But there are also a few patents that seem unusual for banks. Among the more puzzling bank patents cited by La Belle and Schooner are a

These left-field patents raise a question of whether regulators will permit banks to dabble in intellectual properties unrelated to banking. Federal law sharply limits bank holding companies' nonfinancial activities, and that may narrow the scope of which patents they are allowed to use.

Any attempts to treat nonbanking-related patents as financial assets, by licensing or selling them, could run afoul of legal and regulatory rules, Schooner said.

"I don't see how a bank would have the power to develop a patent for something that doesn't relate to financial activity," she said.

So far, however, regulators appear to have shown little or no concern about banks' patent portfolios. Despite the change in bankers' attitudes toward patents, very little attention has been paid to the questions of what banks are patenting and how they plan to use their patents.

It is a subject that merits far more attention, Schooner said, because of big banks' financial and political power a power they demonstrated in the patent-reform efforts.

"Any time the big banks do something new, we should pay attention," she said. "They have a lot of resources, and when they get interested in something they have the power to change that industry, including the laws of that industry."