-

Union Bank in San Francisco and its Japanese parent company plan a series of changes to its corporate names and structure, all in response to the Federal Reserve Board's plan to overhaul the way it supervises foreign banks.

February 28 -

Pressured by overseas governments and institutions, the Fed nevertheless stayed the course in finalizing tough new rules for roughly 100 foreign banks doing business in the U.S. a sign that the central bank's emphasis remains on national stability over international cooperation.

February 18 -

Royal Bank of Scotland has accelerated its plans to sell its U.S. subsidiary. The company will conduct a partial initial public offering of its Citizens Financial Group unit in the second half of 2014, and plans to fully divest itself through offerings in 2015 and 2016.

November 1

It's been nearly two weeks since the Federal Reserve Board issued a new capital rule for foreign-owned banks, and just how far they'll have to go to comply is only getting murkier.

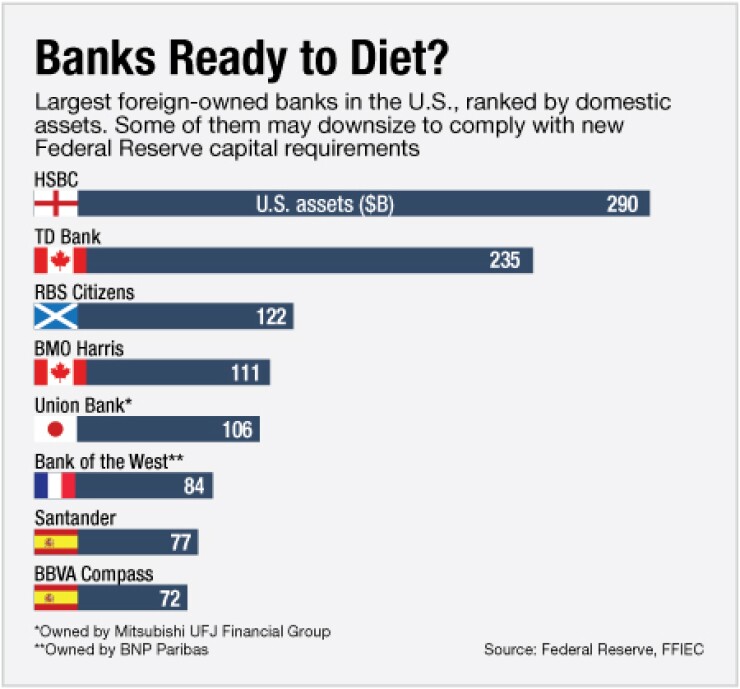

Some foreign banks will seek to sell assets to sidestep the potentially costly rule, thus creating a buying opportunity for rivals, many observers predict. At least one institution, Royal Bank of Scotland's $98 billion-asset RBS Citizens Financial Group, appears to already be taking such steps.

Yet some companies seem confident they're already compliant with the rule, or that corporate restructuring will bring them in line and that they won't have to add further capital. That could be a mistaken interpretation, some experts say.

A bank "needs to be concerned with capital adequacy and leverage requirements," says Ernie Patrikis, an attorney at White & Case and a former chief operating officer of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York.

The Fed rule would

But some foreign banks may attempt to argue they don't need to make many changes. BMO Harris Bank, for example, says it won't need to form an intermediate holding company, one of the Fed rule's main requirements, because it already has one.

Observers expect the issue will be hashed out over the coming months. The rule will apply to foreign-owned banks in the U.S. that have assets of $50 billion or more as of July 2016. They will then get two years, until July 2018, to ensure they have Tier 1 leverage ratios of at least 5%.

The issue may be most pressing to those institutions that hover near the $50 billion asset threshold, says Douglas Landy, an attorney at Milbank, Tweed, Hadley & McCloy who has represented international banks before the Fed and the Office of the Comptroller of the Currency. Those banks are the most likely to sell assets to slim down.

"If you are right around $50 billion and you don't want to grow your business significantly, it makes huge sense to manage it down to $50 billion," Landy says.

To reach the smaller size, these banks may put some assets on the auction block, including branches and loan portfolios, says David Olson, the chairman and chief executive of River Branch Holdings, a Chicago investment bank that represents financial services companies.

"I see a very measured, bank-by-bank approach to this," Olson says. "Some will sell networks of assets. Some will sell particular asset classes."

There are 17 foreign-owned banks that could be subject to the new rule, based on current financial measurements, according to a Fed document released in February.

Among the 17 foreign banks that hold federally insured deposits, British-owned HSBC Bank USA is the largest of the group, with about $290 billion of U.S. assets. Spain's BBVA Compass is the smallest, with about $72 billion of assets.

The rule could impose huge new expenses on these banks. Some bankers have suggested that the initial regulatory costs could reach into the hundreds of millions of dollars, Patrikis says. That's based on the hours required to set up the recordkeeping and compliance for a new intermediate holding company.

There would also be yearly compliance costs, which could reach as high as $50 million, Patrikis says.

Additionally, foreign-owned banks will need to maintain Tier 1 capital of about $2.5 billion for every $50 billion of U.S. assets, Patrikis says. That, too, adds a new layer to the banks' cost of doing business, he says.

BMO Harris says it won't need to form an intermediate company, although the Fed included the $111 billion-asset bank on the list of those that would be subject to the rule.

BMO Harris's parent company, Bank of Montreal, is classified as a foreign financial holding company by the Federal Financial Institutions Examination Council. Below Bank of Montreal on the corporate flow chart sits BMO Financial Corp., which is classified as a domestic financial holding company.

Because it already has a domestic financial holding company, BMO Harris will not need to form an intermediate holding company, nor sell off assets, says Jim Kappel, a BMO spokesman.

"We are not considering the sale of any assets in connection with the Federal Reserve rule," Kappel says.

Even so, BMO and other companies may still need to examine potential asset sales or other means to improve its capital standing, Patrikis says.

"You still might be concerned with liquidity requirements and funding the portfolio," Patrikis says.

The Dodd-Frank Act required regulators to write the rule in order to provide extra protections against potential failures of foreign banks, and to ensure that overseas banks operating in the U.S. are subjected to the same rules as U.S. institutions.

"We retain the responsibility to maintain the stability of the U.S. financial system," Fed Gov. Daniel Tarullo said at a Feb. 18 board meeting.

Foreign banks were among the institutions that accessed the Fed's emergency lending facilities at the onset of the financial crisis in 2008.

All 17 banks on the Fed's list have a domestic financial holding company, just like BMO Harris. A foreign banking organization must form an intermediate holding company, or designate an existing subsidiary, to meet the requirements, according to the rule. The language does not specifically say if a domestic financial holding company would fulfill the terms of the rule.

The Fed's rule may impose higher costs on foreign banks, but the banks may decide it's worth it to take whatever steps necessary in response, in order to remain in the lucrative American market, says Oliver Ireland, a bank regulatory attorney at Morrison & Foerster. The answer is likely different for each bank.

"[Foreign banking organizations] will have to answer that individually, as the amounts are likely to be specific to each," Ireland says.

RBS' Citizens Bank appears to moving toward a sale of assets to get itself under the $50 billion threshold. Royal Bank of Scotland had previously announced that it

The $105 billion-asset Union Bank in San Francisco, a unit of Mitsubishi UFJ Financial Group, has also moved in response to the Fed rule. Last week,

Some foreign-owned banks will find that it's more costly to operate in the U.S. but still worthwhile, Landy says.

"Yes, there are additional disincentives to being in the U.S. now, but there is a huge set of overwhelming advantages for why they are here and those haven't changed," he says.

"They have to do a closer look at the return on equity to determine if you are allocating your funds properly," Landy says. "It's a discipline everyone is going to go through right now."