While many fintech products display rundowns of money already spent, a new app seeks to predict when bank customers’ balances will be low and plans to offer them advances to avoid overdrafts.

Those are just some of the striking details about Dave, a Los Angeles startup with a chummy name that launched its app Tuesday. The company — which has raised $3 million from the billionaire Mark Cuban and other investors — will fund its own advances instead of using a bank partner, and its income will rely on $1 monthly user fees (they start after the first month of use) and voluntary

However, the mission of the app underscores a

Instead of predicting what consumers can save,

When users are paid, the app will automatically grab money owed from their accounts if they agree to it. But users can also pay the startup back manually. And new advances are barred before the previous one is paid, company officials say.

Such services typically raise privacy issues. Dave’s privacy policy says consumers may limit sharing of personal information for joint marketing with other financial companies and for affiliates and nonaffiliates to market to its customers, but they may not block marketing directly from Dave or sharing with affiliates or credit bureaus for everyday business purposes.

Jason Wilk, Dave’s chief executive and co-founder, sees the service as a way to avoid overdraft fees — something he still believes requires solutions despite reforms made in recent years and banks' offering

“The problem isn’t getting any better,” Wilk said.

Although

And sure, banks are required to get consumers to opt in to overdraft fees; however,

“The vast majority of people who overdraft appear to do it by accident or unintentionally,” said Nick Bourke, director of consumer finance at the Pew Charitable Trusts.

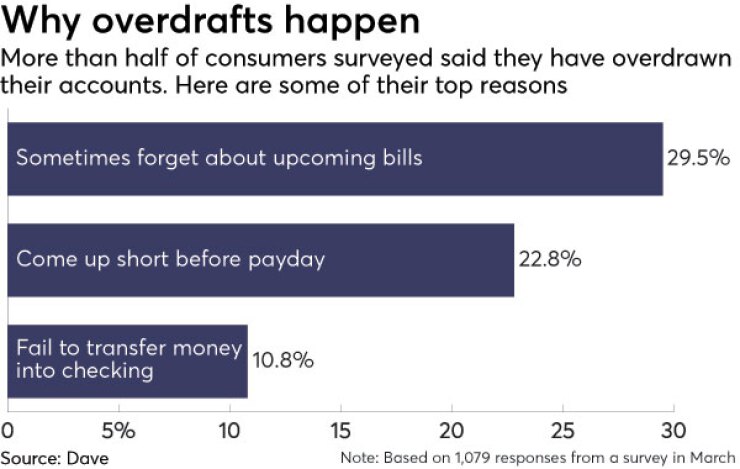

According to a survey Dave conducted in March, consumers cited “forgotten bills” and “I come up short before my payday” as top reasons why they were dinged with overdraft fees.

And as Wilk sees it, there is also a segment of consumers who do not opt in to overdraft protection because they are either unaware or want to avoid using overdraft as an expensive form of credit.

For all of these consumers, Dave is meant to be a cheaper alternative for times when bills are due, balances are low and payday is still a ways off. Besides the monthly $1 fee, there are no interest charges, but Dave asks users to make an optional donation at a time when most overdraft fees are around $34 a pop.

“Our current mission is to enhance existing checking accounts with Dave's technology,” Wilk said.

Regardless of whether Dave lives up to its goal of an overdraft fee remedy, there is no question that consumers struggle with juggling income swings and expenses.

“It’s not a niche issue,” said John Thompson, senior vice president of the Center for Financial Services Innovation. “Spikes and dips and expenses and lack of correlation between [them] put households in situations where they have to scramble to cover those gaps.”

Dave is but the

The name-your-fee model is atypical in finance with a few exceptions. Activehours and the startup

Like the others, Dave is up against many challenges, including courting consumers. In Dave’s case, it could be harder to engage consumers with something that could be considered depressing: low-balance predictions. Wilk casts Dave’s service as a positive experience.

“We are saving people from a very negative" outcome, Wilk said.

As Pew’s Bourke sees it, a paycheck is somewhat of a forced savings device and the jury is still out on whether advances ahead of paychecks actually help someone more than they harm them.

Consumers need to be able to pay small-dollar credit over time so as to avoid a cycle of dependency, Bourke says.

Granted, Dave users do not have to advance a portion of their paychecks. The forecasting feature, after all, is designed to get people thinking about ways to avoid the outcome.

However, forecasting transactions is almost as controversial as offering small lines of credit. Some see forecasting transactions as

Certainly, Wilk is in the camp that believes forecasting transactions will help consumers. As he sees it, apps need to crunch the financial data they have to help consumers better understand their available balance before it is too late to prevent a negative outcome. Dave will also let users pause the predictions as well as alert the app when something is inaccurate.

Regardless of whether Dave flames out or endures, the app’s emergence points to a blending of products that some believe will increasingly gain importance in banking.

“It’s different than it used to be,” Thompson said. Dave "represents an opportunity to solve problems consumers have as opposed to just asking them to solve them on their own.”