For all the gnashing of teeth over the likely effects of low interest rates, net interest margins

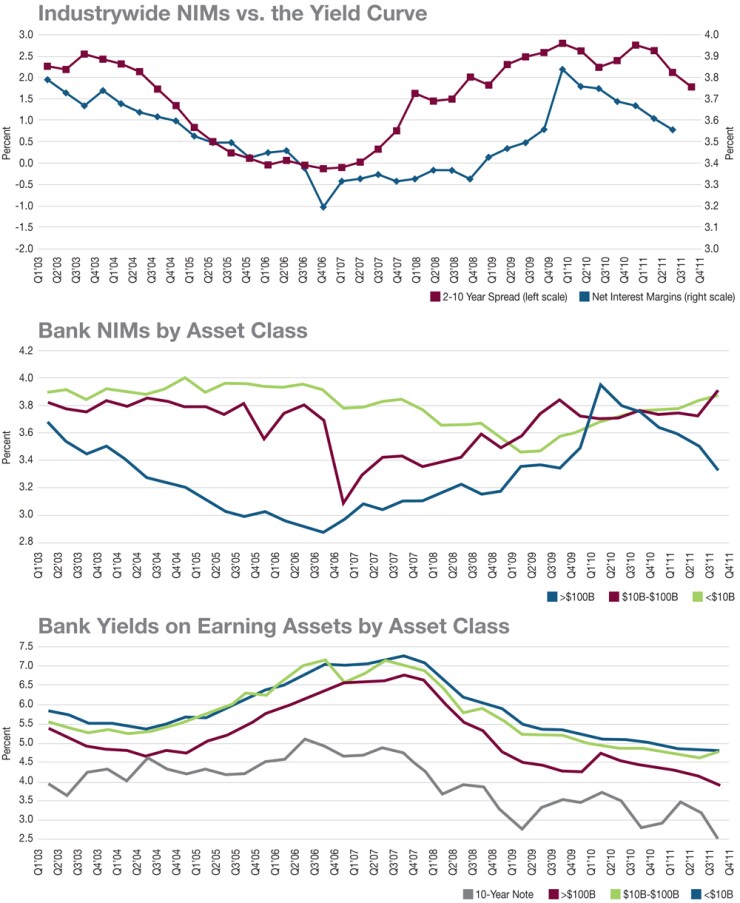

NIMs had been squeezed as the Federal Reserve tightened policy from mid-2004 to mid-2006, flattening the yield curve and hurting profitability to the extent that banks borrow short and lend long. But through the third quarter of 2011, NIMs at banks with less than $10 billion of assets had climbed for 10 consecutive quarters.

A common view is that margins would be caught in a vise as funding costs, moving ever closer to the zero boundary, exhaust their ability to offset falling asset yields. Banks' power to

Lately the reductions have been concentrated among banks with less than $100 billion of assets-these institutions rely heavily on certificates of deposit, which take time to mature and catch up with market rates. Still, even the largest banks achieved a 9 basis point decrease in funding costs from the previous quarter, to 55 basis points in the third quarter.

Preliminary fourth-quarter statistics available at press time provided no confirmation of the more dire warnings about NIMs. KBW's Keefe, Bruyette & Woods found that margins were about flat in the final three months of the year compared with the preceding quarter and the year prior, based on a tally of public banks that had posted year-end results by late January.

It is true that margins at banks with more than $100 billion of assets have been dropping sharply since the first quarter of 2010. That quarter reflected an artificial spike resulting from the

To be sure, interest rate models suggest that many institutions could realize windfalls if yields suddenly lurch up and wash through portfolios of rate-sensitive assets.

Moreover, pessimism about the strength of the recovery and Fed easing have narrowed the yield curve for the last three quarters, generally a headwind for margins.

History has shown that margins are not the creatures of one directional influence, however. To the extent that low rates goose loan growth and allow banks to rotate out of